All Saints by the Lake, Dorval

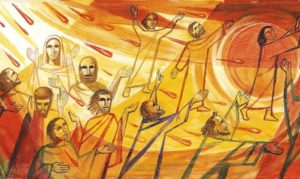

The Day of Pentecost, Year C

June 9, 2019

A few weeks ago, I was on the bus and there were two people having a conversation behind me. It wasn’t in English, so of course, being in Montreal, my brain assumed it was French and first attempted to process it that way. The people involved seemed to be saying the word “champignon” a lot, but just as I was trying to figure out why they had so much to say about mushrooms, I realized that in fact they were speaking Chinese.

Daily life in a multilingual environment – especially when you don’t speak or understand one or more of the dominant languages all that well – is an ongoing challenge, as well as assuring that life is rarely boring. Language is An Issue, in capital letters, here in Quebec in a way that it isn’t in many other places. And in that regard, we can perhaps understand the milieu of the first Pentecost in a more immediate way than many other westerners.

The long list of tongue-twisting place names in the reading from Acts isn’t just a catalogue of exotic places. It specifically describes people coming from the fringes of the empire, from the remoter parts of the Jewish diaspora – north Africa, Arabia (beyond the eastern borders of Roman authority) – from Crete, which had a reputation as a violent backwater despite being in the middle of the Mediterranean, and also, conversely, from Rome itself. The people who heard the disciples speaking in their own languages were specifically those who would have had particular difficulty navigating in the Greek lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean – either those from places so remote that Greek was hardly spoken, or from Rome itself, which clung stubbornly to Latin as proof of its superiority over the rest of the Empire. Language, as always, came with markers of class, culture, and who was in and out.

In our lectionary this morning, the Pentecost story is presented as a response to the story of the tower of Babel in Genesis. The Babel story happens immediately after Noah’s flood, as the descendants of Noah multiply and repopulate the earth. They decide to build a great tower reaching up to the heavens, and in response, God confuses their language so that they can’t understand each other and thus can’t work together on the project.

On the surface, this tale seems to be telling us that a diversity of languages is a bad thing. But what is bad, in Babel, is Babel itself: it is no accident that the name of the tower is the same word as Babylon, the enemy city of empire and exile, the opposite of everything God plans for his people. The people are tempted to settle down (when they have been told to spread through the world), to build something big and impressive enough that they will feel safe and not have to depend on God anymore. God, craftily, frustrates that design by giving them the gift of multiple languages, essentially forcing them to develop many cultures adapted to the many places they find themselves.

St. Augustine famously wrote of the Fall in the Garden of Eden: “O happy fault, which merited so great a Redeemer!” (Since it’s Pentecost, here’s the original Latin: “O felix culpa quae talem et tantum meruit habere redemptorem!”) One could apply the same principle to Babel: the impulse to build the tower was wrong (the fact that the people made bricks, a foreshadowing of the same activity they were forced to do in slavery in Egypt, is a pretty clear tell), but the result of that impulse, when God intervened, was greater than what would have happened if the wrong choice had not been made in the first place. Instead of one culture, one language, one way of being human, we have many, in an infinite, divinely given variety.

Hence, to portray Pentecost as a “reversal” of Babel is to bark up the wrong tree. It is, rather, the redemption of Babel, the same way that the Incarnation did not reverse the Fall, but rather literally made it good. At Pentecost, the multitude of human languages becomes, instead of a barrier to understanding each other for the purpose of thwarting God’s will, a means of understanding each other for the purpose of telling God’s story. The Spirit does not magically make all the people assembled in Jerusalem speak the same language. Instead, She makes the languages mutually comprehensible, while retaining the glorious and irreplaceable diversity they represent. The story of Pentecost is not a story of homogenization, but of translation.

And so, in this province and city where language is both fraught and celebrated and where translation is a daily concern, what new languages might we need to explore in order to tell God’s story? Might we have to learn the language of a different cultural group, a different generation, a different background, even a different religion? Might we have to decide that some things we used to think were offensive aren’t, and some things that used to be generally accepted are actually quite offensive? Might we have to find new words for old concepts, and risk looking a bit foolish, even being accused of being drunk at nine o’clock in the morning?

As a church, we can no longer count (if we ever could) on being able to speak the language we are familiar with and be readily understood. But we still have a story that we are longing to tell, and which the world desperately needs to hear. The Holy Spirit is at work in us, and will give us the words to speak if we are open to Her leading.

The gift of languages given at Pentecost is a gift to those outside the faith community, given specifically for the purpose of inviting them in. We all know the feeling of hearing, in the midst of a random babble of languages that we understand imperfectly or not at all, a sudden phrase or sentence in our own mother tongue. How can we, as a faith community, translate God’s story to those who have never heard it – or heard it only in ugly and damaging ways – that gives them that feeling of deep-down relief of hearing words in their native language?

May the Spirit grant us the gift of translation, and may we always be open to Her moving, in our lives and in the life of this community.

Amen.

Leave a Reply