All Saints by the Lake, Dorval

Proper 12, Year C

June 23, 2019

This past Friday was Indigenous People’s Day, which Montreal observed by, among other things, renaming Amherst Street to Atateken Street, a word that means “siblings” in Mohawk. As a graduate of Williams College in Massachusetts, deathly rivals of Amherst College, I heartily approve of this decision.

But in all seriousness, if Lord Jeffrey Amherst was half as cruel and bigoted in real life as history describes him being, his name should be taken off everything that currently bears it. It should go without saying that we do not name things after people who deliberately infected other people with smallpox.

As you probably know, I spent the week before last in Winnipeg at the Canadian School of Peacebuilding at Canadian Mennonite University, auditing a course called “Indigenous Perspectives on Salvation, Repentance, Peace, and Justice.” The class was taught by Ray Aldred, a Cree scholar and pastor. It was intense – about 30 hours of class time over the course of the week – and I learned a lot, both in terms of the facts of history and the theoretical framework to interpret it.

And when I read the scriptures assigned for this week, I realized I could hardly ask for a better opportunity to share some of that learning with you. Because the whole question of how we pursue reconciliation between groups that are different, and that have hurt each other in the past, is an important one for Christians because we are trying to take seriously the passage from Galatians: “As many of you as were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.”

Which is a beautiful and fundamental sentiment, but much, much more difficult to put into practice than it is to read in church. Having identified reconciliation as one of this parish’s callings, though, it is incumbent upon us to really dig into what it means and how we can begin to live it out.

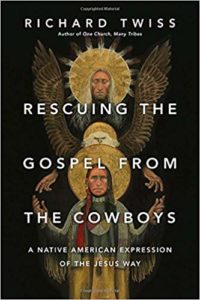

I don’t have many definite conclusions or a grand plan. I do have a number of thoughts about what I learned that I think can help us to understand how our Indigenous siblings have experienced the gospel and understand their relationship to scripture, creation, and those of us who now share this land. These ideas come from Ray and the readings he assigned in the class, but any misunderstandings are entirely my own.

We learned, first and foremost, that indigenous identity is based on relationship: relationship with the land and with all other living beings. All other beings are relatives, and all depend on the land that has been given by the Creator. Culture is rooted in language and story, transmitted orally across generations.

When Europeans arrived on these shores, they were welcomed and offered treaty relationships, which to the Indigenous mind means becoming family. (In our classroom in Manitoba, we were on Treaty 1 land.) One of the fundamental misunderstandings between the cultures that made the treaties was that the Europeans saw them as black-and-white legal documents and the Indigenous saw them as open-ended relationships, always subject to change and evolution – rather like the covenants between God and the people in scripture.

As so often happens when the Gospel is brought to a people as part of a process of colonization, its power transcended its misuse as an instrument of domination and control. The Indigenous people who heard the story of scripture heard in it the note of liberation, just as the enslaved Africans of the New World did – however hard the missionaries tried to act as though becoming Christian meant renouncing Native identity and becoming civilized on white Western terms. The Aboriginal people thought that if this story of God’s life-giving, liberating, reconciling love was the governing story of the people who were coming to their land, those people must have something good to offer. Hundreds of years later, it is not too late to live into this promise and to let ourselves learn about the Gospel through Indigenous eyes, as a story, rather than as a system of rules on how to be pious and compliant.

Reconciliation does not mean we all become the same – quite the contrary. God rejoices in our diversity. We do not need to convince each other of our own rightness in order to be in community; what a liberating thought! We remain male and female, Jew and Greek, settler and indigenous, while also being clothed with Christ and rejoicing in our unity. And our complementary gifts enrich that unity. We can be interdependent without being identical.

One very important distinction on the path to repentance is the difference between guilt and shame. As Ray described it, guilt is an objective state. You did something wrong; a court of law could find you guilty. Shame, on the other hand, is an emotion, and often a motivation for our behaviour. Shame can even be healthy, if it leads us to seek to right the wrong we did and make amends. When shame becomes toxic is when it has nowhere to go. For Indigenous people, there is a burden of unwarranted shame about being who they are, and salvation consists of learning to rejoice in their God-given identity. For the settlers, shame often curdles into anger – the anger of the perpetrator against the one they have abused, anger that stems from the deep-down awareness that we have done wrong and that we need to repent and change (but that would be hard, and we don’t want to do it, so we lash out instead).

Repentance – the acknowledgement on the part of the perpetrator that what they did was wrong, and hurtful; followed by the genuine commitment to change – is necessary before reconciliation can be complete (or, arguably, even before reconciliation can begin). The church is, after all, in the repentance and forgiveness business, and should be able to teach the rest of the world how it’s done. But all too often we have proved just as reluctant as everyone else to do the hard work of acknowledging and articulating wrongdoing and offering genuine forgiveness. Perhaps we can begin by practicing that hard work on the small, low-stakes issues of church life, as a way of beginning to build spiritual muscle for reconciliation on a grand scale.

“And if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise.” The Indigenous understanding of community and covenant as rooted in family relationships echoes the priorities expressed in our sacred story itself. It is that sacred story, and our participation in it through baptism, that unites us. And if we can truly listen and strive to understand, we have much to learn from each other.

For the Aboriginal peoples of this land, salvation is becoming your true self in community; justice is wholeness; peace is harmony with creation and the creator; and repentance is a vision of what life would be like if we loved with our whole hearts, holding nothing back.

I am thankful for what I was able to learn – thanks to all of you! – this week, and I hope to be able to continue learning, and to be accompanied on that journey by this community, so that we may all grow together into Christ, our Lord, whose mission it is to reconcile all things to each other and to himself in God.

Amen.

Leave a Reply