All Saints by the Lake, Dorval

Year C, Proper 21

August 25, 2019

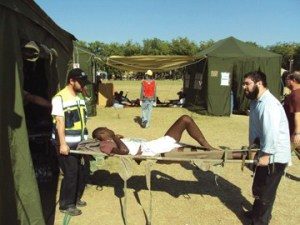

When a massive and catastrophic earthquake struck Haiti in 2010, aid and relief groups from around the world rushed to the stricken island. Among them were teams from Israel, some of whom were highly observant Orthodox Jews. As you probably know, the strict observance of the Jewish Sabbath involves abstaining not only from work, but from cooking food, using lightswitches, driving cars, or riding in elevators, among many other activities.

The earthquake struck on a Tuesday. In the days immediately following, rescue teams dug frantically through piles of rubble while there was still the possibility of retrieving people alive from the wreckage and getting them to medical treatment. For three days, the Israeli teams worked along with the others, 24/7 in the sweltering tropical heat, wearing long sleeves and skullcaps in accordance with their custom. On Friday evening, as the Sabbath began, they paused to say the traditional prayers.

And then they picked up their shovels and got back to work. Because while one person might be waiting to be hauled out from under a mound of broken concrete, these ultrareligious Jews were – as the Israeli papers reported at the time – “proudly desecrating the Sabbath” in their lifesaving mission, which was as much a part of their religious tradition as complete rest would be under ordinary circumstances.

It is this understanding to which Jesus is appealing when he responds to the leader of the synagogue who has criticized him for healing on the sabbath day. Yes, the woman has been suffering for eighteen years and the outcome would probably not have been significantly different had she waited another twenty-four hours (unlike someone dying of dehydration under a pile of rubble in Haiti). But the point that the leader of the synagogue is missing is that the sabbath has always been about healing and saving life.

Sabbath has not exactly been a prominent feature of our cultural life in the western world for the last century and a half or so. We read in Victorian novels of the dour sabbaths of that era, when you went to church twice and were permitted only to sit around in your best clothes and perhaps read improving literature, in between. With the loosening of social mores toward the end of the nineteenth century, those restrictions were happily discarded along with all the rest, and gradually stores, sports teams and other institutions started treating Sunday like any other day. What replaced the nineteeth-century Sabbath was a culture of 24/7 workaholism and the worship of productivity, which has made people sick, impeded full human flourishing, and incidentally contributed to the ecological crisis, thanks to ever-increasing materialism and consumption.

In the last decade or so, the idea of “self-care” has entered (or perhaps re-entered) the lexicon, but the idea that health and sanity can be maintained through the occasional spa day or glass of wine in the bathtub falls far short of what God is trying to tell us through the commandment to remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy.

(That said, I think the Quebecois, with their well-established habit of disappearing into the woods for multiple weeks in the summer, may have figured something out about sabbath that my people, the Puritan Work Ethic New Englanders, have not.)

Sabbath is about rest, yes, and rest good and holy, and something we almost all need more of. But it is also about affirming something more profound: the godhood of God and the finitude of humans. It is about reminding ourselves that ultimately, God is in charge and it is not up to us to save (or destroy!) the world. Sabbath is about being rather than doing.

One of the reasons that observant Jews abstain from so many ordinary daily activities on the Sabbath is the idea that for that one 24-hour period, they refrain from altering the world. They let things be as they are. They devote themselves to prayer and let God do the changing, if any, while humans stay hands off. It is a surprisingly radical thing to do, and a profoundly important corrective to our hustling, restless, never-satisfied culture, which insists that you must be out optimizing everything, chasing your dreams, and changing the world all the time, or you’re doing something wrong.

And so when Jesus heals on the Sabbath, it is not only an affirmation that some things (like saving lives) are more important than sabbath observance: it is also an affirmation of Jesus’ identity as God. Even if humans choose not to heal on the Sabbath, God does.

And humans can make legitimate choices about how to craft their own Sabbath observance in the most meaningful ways. When US Senator Joe Lieberman was running for Vice President in 2000, he was questioned about his Judaism, and told reporters that he only did “work for the good of the world” on the Sabbath. I was once taking the T in Boston and a medical resident, wearing scrubs, asked me to swipe his CharlieCard for him; he was clearly OK, on some level, with working a shift at the hospital on the Sabbath, but he still reminded himself what day it was by drawing the line at the mundane task of interacting with the turnstile.

Elsewhere in the Gospels, when Jesus is criticized for sabbath-breaking, he replies, “The sabbath was made for humankind, not humankind for the sabbath.” In other words, if our sabbath rest is not genuine, fruitful, fulfilling rest, we have missed the point (as any Victorian child dressed up in uncomfortable clothes and parked on an uncomfortable chair with nothing to do all afternoon on Sunday could tell you). Any rules we make about our observance should be in the service of ensuring that our sabbath is genuinely an experience that fills us up and brings us closer to God. And sometimes, that involves bringing a fellow child of God out of an affliction from which they have been longing to be released.

Because there is an aspect of Sabbath that is even more foundational than Sabbath as rest, as prayer, and as non-intervention, and that is Sabbath as liberation.

Sabbath rest is one of the Ten Commandments, and the Ten Commandments were given while the people of Israel were wandering in the desert after escaping from slavery in Egypt. It was part of the process of God bringing them out of their slave mentality and forming them as a free people.

One feature of the Hebrews’ slavery was its relentlessness. To the Egyptians, the enslaved Hebrews were not human: they were just brick-making machines, kept to their tasks around the clock, seven days a week, with continually increasing quotas and no straw. There was no life outside of work, no purpose other than productivity and trying to avoid punishment.

And so when God was transforming them on their desert journey, the first thing they heard, after “I am the Lord your God and you shall worship me alone” was the command to keep the Sabbath. Because a free people can choose not to work. A free people can make the decision to prioritize things other than raw productivity. And this doesn’t just apply to the bosses and the elders: not only the head of the household rests on the sabbath, but your sons and your daughters, your ox and your ass, your manservant and your maidservant and the sojourner within your gates. No one is excluded. There is no one lowly and invisible enough to have to shoulder the burden for everyone else, to have to do the dishes in the corner in order to keep all the others comfortable. The Sabbath rest is universal. The Sabbath rest humanizes the dehumanized, frees the oppressed, and restores the broken. The Sabbath rest is far more than rest; it is liberation.

So yes, we should consider Sabbath for the sake of rest and self-care and a countercultural opting-out from the cult of productivity. But most fundamentally, with Jesus as he confronts the leader of the synagogue, we should be asking: is our Sabbath liberating those who are in bondage? And if not, how can that change?

Amen.

Leave a Reply