All Saints by the Lake, Dorval

Year C, Proper 24

September 15, 2019

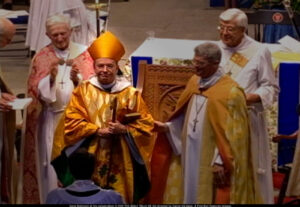

Bishop Gene Robinson wearing “all that stuff” at his consecration, November 2, 2003

“I am grateful to Christ Jesus our Lord, who has strengthened me, because he judged me faithful and appointed me to his service, even though I was formerly a blasphemer, a persecutor, and a man of violence.”

Paul’s conversion story is one of the most dramatic and personal narratives in the whole Bible, and has understandably become a paradigm for the Christian life. From the lost sheep and coin in today’s Gospel to the writer of Amazing Grace, we are taught to appreciate and emulate stories of the one who was lost and is found, who was blind but now sees.

But where does that leave those who have no such dramatic story to tell?

This is a question with personal resonance for me, because when it comes to church I’m the ultimate insider. Not only was I baptized at four months, confirmed on my thirteenth birthday, and ordained at 29, I never wandered away from church as a teen or young adult, or even did so much as try another denomination, except for my two years on assignment with the Lutherans in 2016-2018.

There are entire Christian denominations that essentially require all their members to have a conversion experience, “getting saved” or “inviting Jesus into their hearts”, as part of their journey to maturity in faith. But for many believers, that does not reflect our experience. And indeed, by baptizing babies in the Anglican tradition, we hope to create for many an experience of faith whereby we do not remember ever being “lost” before we were found and embraced by God and God’s people.

And of course just being a church insider doesn’t insulate you from the experience of feeling lost and alienated, or of being found and welcomed home. And all too often, in two thousand years of history, it has been the Church that has been kicking sheep out of the fold, rather than wandering the desert hillsides looking to bring them back.

If we are to find life and meaning in this text rather than forcing everyone into the same mold of conversion which may or may not fit, we must look at the question of who’s in and who’s out, who’s lost and who’s found, who’s wandering far and who’s bringing them home, as flexible and ever-changing. Sometimes we will feel lost, and need to be brought back. Sometimes we will go looking for others. Sometimes the church lives into Jesus’ infinite welcome, and sometimes it falls far short and behaves more like Saul pre-conversion, a blasphemer, a persecutor, and a person of violence.

We had a fascinating conversation about this as Bible study on Wednesday, with people sharing their own experiences of wandering and homecoming, losing and finding. As usual, Bob spoke eloquently about his ministry in the prisons, and how sometimes the gatherings in that bare-bones chapel can feel more like church than some of what happens in Gothic buildings with glorious stained glass and all the ecclesiastical trimmings.

Being lost and being found by God doesn’t always map neatly onto our social expectations of who’s in and who’s out – and indeed, it shouldn’t, and we should be very alarmed if starts to. By definition, the sheep that the shepherd is seeking in the wilderness in Jesus’ parable isn’t the person with a lot of political, social or financial power; they’re the one who is helpless without the shepherd to find and care for them. For Paul, being found by God meant losing all his accumulated religious, intellectual and social capital from years of achievement and excellence in his native culture, and throwing his lot in with the ragtag bunch of outcasts following what was then known as the Way of Jesus. We always need to pay attention to the power dynamics at play in the story.

When Bob mentioned finding deep meaning in those prayer services in the prison chapel, it put me in mind of the movie For the Bible Tells Me So, a documentary about the experiences of a number of different gay Christians, one of whom is my former bishop, Gene Robinson, the first openly gay bishop in the Anglican Communion. Gene’s consecration took place on All Saints’ Sunday, 2003, in the cavernous hockey arena of the University of New Hampshire, and was attended by many interfaith guests (and, sadly, also by a number of police snipers, since Gene and his husband Mark had received credible death threats in the days leading up to the service).

As is customary in Anglican ordinations, Gene, as the candidate, began the service in a simple white alb, and midway through was vested in the full regalia of a bishop: gold stole, cope, mitre, and crozier. It was a powerful statement of inclusion and authority for one who represented a group that until that moment had been entirely excluded from the corridors of ecclesiastical power. In the movie, one of the interfaith guests, a gay Baptist man who had shared many of Gene’s struggles, remarked of that moment, “When I saw Gene out there in front of everybody wearing all that … stuff, that’s when it really hit me. We had arrived.”

The church has not always been good at figuring out who the lost sheep are who need to be found, or welcoming them when they are found, or honouring the journeys of those who never particularly needed to be found in the first place because they were already here. But I think that the prayer service in the prison and the vesting of the first gay bishop point us to an important truth: that even if the church has no other reason for existing, it exists to provide the power and meaning for those moments. Part of the resonance of the prayer service in the prison chapel comes from the fact that day in, day out, imperfectly but faithfully, God is worshipped in spaces of beauty and dignity, and when the same worship takes place in a cinder block room among men held behind rolls of razor wire, it partakes of that same holiness. Some of the power of the moment of Gene’s vesting as a bishop comes from the fact that for centuries, those vestments were reserved for privileged, straight (or closeted) men who wielded power in the name of the church – often wrongly, even sinfully, but the power was still there, and the power actually partakes more fully of God’s will when it is given away to those who have formerly been excluded.

The Lutheran theologian Gordon Lathrop writes of the “broken symbol” – the idea that all aspects of the life of faith, all of our symbols and stories and rituals, must be treated like the communion bread; they must be continually broken and given away, or they will lose their power and become idols. The prison prayer service and the vesting of the gay bishop derive their power from the parish worship service and the centuries of ecclesiastical authority – but more to the point, the parish worship service and the centuries of ecclesiastical authority are meaningless without a prison chapel and a gay candidate (wearing a bulletproof vest under those vestments) to which they can be extended.

We do not seek the lost to bolster our institutions or make ourselves feel better. We seek the lost because that is where God is. We break our holy things and give them away because that is the way – the only way – that they are made holy.

You’ll notice that, when the shepherd finds his sheep and the woman finds her coin, they don’t just go back to normal, let alone hold more tightly onto these valuable things because of the scare of having lost them. Instead, they rejoice! They celebrate! They call those whom they love and throw a party – which, you have to suspect, probably costs more than the coin or the sheep did in the first place. But that’s the point, isn’t it?

We here at All Saints’ are just beginning to figure out how to live into our motto, “Reconciling, Affirming, Rejoicing.” And that third word, Rejoicing, often gets short shrift. But here they all three are, in the parable of finding what is lost: bringing things together. Embracing the vulnerable and the odd one out. And then throwing a party, for the sheer fun of it, because why would we not celebrate when God does amazing things, upends our expectations, breaks open the holy things, and brings us all home?

Amen.

Leave a Reply