All Saints by the Lake

St. Michael and all Angels

September 29, 2019

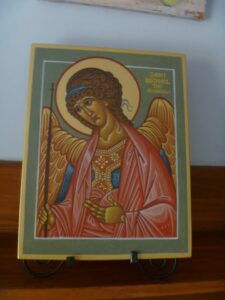

The icon of St. Michael the Archangel I presented to my curacy church as a departure gift in 2011.

Why should we care about angels in 2019? Why should we march around the church singing a hymn with a lot of odd-sounding and outdated ideas about spiritual warfare? I mean, it’s kind of fun, but other than that?

Well, for one thing, angels are hip these days, so there are a lot of ideas about angels out there. And one pervasive idea is that people become angels when they die.

The only thing one can say about this, from the perspective of traditional Christian theology, is that it is not true. It’s understandable, given that we often talk about saints and angels in the same breath; but they’re not the same thing. Angels are a completely different order of being from humans; the word comes from the Greek angelos, meaning “messenger” (the same root as “evangelism”), and angels are purely spiritual beings, portrayed in art as beautiful to reflect their closeness to God and winged to represent the speed of their passage. In scripture, when angels appear to people, the first thing they say is invariably “Do not be afraid,” because to be visited by an angel is a fearsome thing.

And this isn’t just an academic discourse about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. It’s far too common for people grieving the loss of a loved one to hear “God needed another angel” as an attempt to offer comfort – as though God took pleasure in taking our loved ones because there was a job vacancy in heaven. I know far too many parents who have lost children, in particular, who have been deeply offended and disturbed to be told that their child is now an angel. Our words of comfort to the grieving need to be focused on sharing their sadness, not trying to make it go away.

Those whom we love, but see no longer, do not cease to be human thereby; they become, not angels, but saints. And of course we have chosen to call our congregation All Saints, and thereby make the saints central to our identity. We believe that all the faithful, past, present and future, are united in that one communion; and that in the world to come, we will all have grown into the full stature of who God intended us to be, whether our life on earth ended after more than a century or before it had even begun.

Today is the feast of St. Michael and All Angels. (Yes, we call some of the named angels “St. So-and-So” – I did admit it’s confusing!) In six weeks, we will celebrate All Saints’ Sunday, and for the first time it will be our “feast of title”.

This time of year is what the Celts, in their ancient spiritual wisdom, called a “thin place” – where the veil between the present and the eternal becomes almost translucent, and we feel that we can get a glimpse beyond. As the days darken and grow colder, as the trees show their leafless bones and the autumn winds blow, our faith, with the sure instinct of paradox, presents us with images of faithful endurance unto and beyond death, of winged angels and crowned saints, of the faithful shining forth like sparks through the stubble and the holy city coming down from God in bridal perfection, and of death being conquered by God’s resurrection power.

It begins today, with the angels, God’s heavenly messengers. Next week, St. Francis’ Day, with the Pet Blessing, and the following week, Thanksgiving and Harvest, remind us that heavenly things are eternally bound up with the earthly things; that we await a new creation, not the annihilation of creation; that the humble things of earth, animals and plants, pets and harvests, the reaped earth and the turning leaves, are infinitely loved by God.

At the hinge of the year, the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, the Christian Halloween revels in death and fear and madness precisely as a way of showing these powers of darkness that they have no final hold over us; and then All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days, November 1 and 2, bring us up out of the pit where the zombies and werewolves dwell, clothe us in white robes, crown us with gold crowns, and remind us that Christ has conquered death in each and every one of us. And then the feast of Christ the King, at the end of November, ushers out the autumn in a blaze of heavenly glory, giving us a glimpse of what we hardly dare to hope for, that at the end of this mortal pilgrimage something awaits us that is beyond our wildest dreams.

This time is a reminder that however much we may love this mortal life, and however hard and well we may work to make the world a better place for those who are now in it – ultimately, we are all made and meant to long for something we can’t see, to peer beyond the door of death and decay and glimpse a promise of glorious immortality.

Angels and animals, spooks and leaves, life and death, creation and resurrection, decay and glory – at this time of year they collide, and give each other new meaning, and teach us about the paradox and the anguish and the hope of being human, of being mortal, and of hoping for something more.

A couple of years ago, I was suddenly visited with the inspiration for a set of vestments designed for this season of the year, this later post-Pentecost when we drive the altar guild nuts switching between green and white on, it would seem, a weekly basis.

The chasuble would be a fairly detailed crazy quilt of colors and images, but with clear bands or zones layered from top to bottom. Starting from the bottom edge of the vestments and working upward, you would begin with earth tones, brown dead rotting leaves, bugs and worms and grey skeletons (human, but also animal, since this time of year is also the traditional slaughtering season, observed in Europe on St. Martin’s day, which as it happens is also Remembrance Day, November 11) and maybe a couple of tombstones. That would transition into a mostly-green segment for harvest and creation, with animals and ripe grain, apples and gourds. That, in turn, would melt seamlessly into a zone of autumn leaves – brown, purple, red, orange, gold, yellow – with the leaves growing subtly lighter as you went up, until, around chest level, they finally transitioned into the white band for All Saints’/Christ the King, which would be slightly more abstract but clearly suggestive (in gold and red outlines and accents) of wings, flames, robes, and crowns.

Creation, harvest, slaughtering, death, decay, shortening days, turning and falling leaves, Halloween, saints, angels, heaven, kingship, glory. All the themes are there, and to me, the fact that they work artistically goes a long way toward proving that they work theologically, liturgically and spiritually: that the church’s instinct was correct all those centuries ago when she placed St. Michael’s Day at the beginning of the harvest season, and first grafted the feast of All Hallows onto the Celtic Day of the Dead.

And it all starts today, with the angels; with God’s messengers, sent to call us humans into God’s story and announce God’s will. The angels who surround God’s throne, who go up and down Jacob’s ladder, who defend the saints from the powers of deception and death. The angels who will not convert us into themselves, but who will rejoice with us before God, saints and angels together, in the new creation.

Amen.

Leave a Reply