All Saints, Dorval

December 24, 2019

The Christmas before I was ordained, I went to a concert presented by the Yale Camerata. The second half was the sixth and final part of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, and I described the very end (on my blog – remember we all had those in 2007?) as follows:

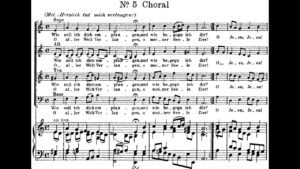

Last chorale, grand finale, off we go with the orchestra tooting away in 4/4 in a major key and the brass being all flourish-y and rejoice-y – and then in comes the choir in four-part, four-square chorale harmony, and what’s the chorale tune? Herzlich tut mich verlangen. (A hymn that we sing on Good Friday, that goes into great detail about the agony of Christ’s death on the cross.)

I had about two and a half measures of thinking, “What the heck? This is really weird and not very appropriate, and surely they had more than three chorale tunes for Bach to choose from for this movement?” and then I regained my sanity and realized that of course Bach was just being a genius, as was his wont. Placed at the climax of six whole cantatas celebrating the Incarnation, in a setting that sustains the overall theme of joy and festivity, here is a subtle but unmistakable reminder of the inevitable consequences of the Incarnation – the Passion. The story doesn’t end with the Three Kings bringing gifts to the baby and all the morning stars shouting for joy.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember about this oh-so-familiar story is, precisely, that it doesn’t end there. The Incarnation – the birth of God into human flesh and time – is good news not because one young woman in Bethlehem got to cuddle a new baby, but because as a result of this birth, nothing would ever be the same.

But God, for God’s own inscrutable reasons, chose not to come to us in power and might and, in Dorothy Sayers’ phrase, “smite the world perfect.” Instead, God came to us in weakness and perfect goodness, and the world did to God what the world normally does to perfect goodness.

The British writer Ursula Fanthorpe wrote this wry poem titled “The Wicked Fairy at the Manger” on a Christmas card to a friend. (Please note that it contains one old-fashioned slur that I would not use if I weren’t quoting.)

My gift for the child:

No wife, kids, home;

No money sense. Unemployable.

Friends, yes. But the wrong sort —

The workshy, women, wogs,

Petty infringers of the law, persons

With notifiable diseases,

Poll tax collectors, tarts;

The bottom rung.

His end?

I think we’ll make it

Public, prolonged, painful.

Right, said the baby. That was roughly

What we had in mind.

God knew exactly what God was doing, and had a pretty good idea of how it would turn out. When it encounters perfect goodness, the world tends to treat it with remarkable cruelty. And perfect goodness does so often look like weakness – like a helpless newborn in a feedbox, like a man faithfully taking care of a child he knows isn’t his, like a woman cradling the baby she already knows, on some level, she must lose.

The British graffiti artist Banksy recently unveiled a work entitled “Scar of Bethlehem,” which at first glance looks like a typical nativity scene, but on second glance, the backdrop behind the Holy Family reveals itself to be a section of the border wall that bisects present-day Bethlehem, and the star hanging over the manger is actually a hole blown in the wall by a mortar.

Emmanuel, God with us, was born into a world very much like ours, a world rent by conflict and dominated by empire, where the poor kept getting poorer and divisions of class, creed, language, and culture caused explosions of violence. And his birth was only the beginning of his confrontation with the powers that be: a confrontation that ended with his betrayal, trial, and execution – and then, three days later, with the plot twist to end all plot twists. There was no other way that the showdown between perfect goodness and the powers that be could end. The event of the Incarnation encompasses both the heart-bursting joy of a perfect newborn sleeping peacefully in his mother’s arms, and the heart-splitting agony of that same body broken, thirty years later, on the cross. Neither, in fact, is possible without the other; and both come to completion only on Easter morning.

In case the accidental birth between the livestock didn’t convince you, knowing what happens to this child after he grows up makes it clear that God did not come to earth to prop up the existing power structures or to tell people that they’re only right with God if they’re healthy, clean, and happily married with 2.5 children and a retirement account. God comes to earth for all of it – our hallelujahs and our horrors, our distractions, messes and confusion, the ways we don’t fit in, the things that don’t go according to plan, and the moments of joy, delight and connection in the midst of it all.

Our job, after worshiping the babe in the manger, after witnessing perfect goodness defenseless against the powers of this world, is to figure out how to reflect that goodness in our own lives. How do we, in our own small way, follow the Saviour who chose to come in weakness rather than in power, to be with us, to heal, to feed, to comfort, and to rescue us from death? How do we shine the same light into the shadows of the world, that shone from the star over the byre in Bethlehem?

Each of us will have a different answer. But our answer will be richer for remembering that tonight is only the beginning of the story, and that its end is on the hill of Calvary and in the garden on Easter morning – and, finally, in that second Advent, in which this child will come again to make all creation new.

And so we end with another poem, this one by Luci Shaw, titled, “Mary’s Song”:

Blue homespun and the bend of my breast

keep warm this small hot naked star

fallen to my arms. (Rest …

you who have had so far to come.)

Now nearness satisfies

the body of God sweetly. Quiet he lies

whose vigor hurled a universe. He sleeps

whose eyelids have not closed before.

His breath (so slight it seems

no breath at all) once ruffled the dark deeps

to sprout a world. Charmed by dove’s voices,

the whisper of straw, he dreams,

hearing no music from his other spheres.

Breath, mouth, ears, eyes

he is curtailed who overflowed all skies,

all years. Older than eternity, now he

is new. Now native to earth as I am, nailed

to my poor planet, caught

that I might be free, blind in my womb

to know my darkness ended,

brought to this birth for me to be new-born,

and for him to see me mended

I must see him torn.

Amen.

Leave a Reply