All Saints’, Dorval

April 11, 2020

In an ordinary year, it’s easy to forget what the church actually is: that we are part, not of just another volunteer organization with a few odd rituals on Sunday morning, or even of a group of people doing our best to find our spiritual centers and lead good lives – but part of a cosmic struggle, a battle of good against evil with eternal consequences.

This, however, is no ordinary year. This year, the powers of death are very real and very near. This year, it takes little imagination to envision ourselves in Sheol, in the dark, silent place of the dead envisioned by the Hebrew Scriptures – or in the livelier and more medieval version of hell, with its flames and demons and tortures. This year, the cosmic battle between the powers of life and death is happening all around us.

And in that battle, God does not just sit above the fray in heaven issuing moral directives and keeping score. The church has insisted from the very beginning, that in Christ, God went undercover, for all the world like Aragorn in the Lord of the Rings, the heir to the throne disguised as an ordinary drifter – took on a last-ditch mission to rescue humanity when all else had failed, and humanity, in cahoots with the powers of evil, caught him and put him to death.

At which point, death, or hell, or the devil (however you choose to conceptualize it) thought that things were going pretty darn well. Even God had succumbed to the power of death! Death was in charge, and could have all the toys, and call all the shots, for all eternity!

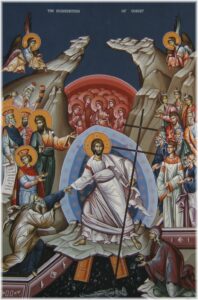

And Death happily gloated in this vein for, oh, maybe 30 hours or so – right until God showed up on the doorstep of hell, blew the bolts off, walked right over the doors, and fetched out all the faithful people who had been waiting there for thousands of years. (For a visual depiction of this moment, known in Eastern iconography as the Anastasis, wait for the slides accompanying the last hymn tonight.)

This night is the Passover of the Lord, the Harrowing of Hell; the breathtaking, addictive last few pages of the long fantasy novel, when everything is going wrong, the enemy has won, the evil magic is taking over the world, God has died – and then, when all seems lost, the hero remembers that last scrap of magic that his trusted teacher told him on page three – and throws it in the monster’s teeth, and the evil spell snaps, and death itself begins working backwards. In the grand, pithy paradoxes of medieval English poetry: “He that comes despised shall reign; he that cannot die be slain; death by death its death shall gain.”

If we were doing this in person, we would have gathered in the church in the pitch dark, and after telling all the best old stories of God parting seas and raising bones, we would have taken our little candles and gone out, into the black night, and marched around singing, calling on the presence of all the saints and all those we love who have gone before us, leaving our darkness and bondage and emptiness behind and setting out on the long journey across the Red Sea, to the land we have been promised, to the place of light and beauty and love and joyful noise, where resurrection is a reality. And when we came back, the church would have been transformed, blazing with light and decked with flowers, and the organ would ring out and we would all be together with our bells and noisemakers, shouting Alleluia.

But we’re not doing this in person. And so our Easter joy and our Holy Week grief are mingled this year in a way they never have been before. But if there is one thing that the Great Vigil of Easter teaches us, it is that we don’t need sunshine and Sunday morning for the resurrection to be real. The victory takes place in the dark, in the depths of the earth. I think that’s why I felt so compelled to do this service this year, even though it hasn’t been part of All Saints’ tradition recently.

This night is the hinge, between death and life, between mourning and rejoicing, between hell and heaven. The Resurrection does not immediately and magically make everything better, just as the full moon riding among the clouds outside does not light up the world like the sun. We believe that God has acted in the world, decisively, once for all, to break the power of death and hell. But all too often – and especially now – that victory seems veiled, like a flower still tight in the bud, like a moon veiled by clouds, like a handful of people on Zoom in the middle of the night to tell stories and sing songs.

But our Savior has come down into hell to find us and lead us out, and so even if the night is full of chaos and horror, we know that these forces will not have the last word. We have been led out of hell, through the flood, over the Red Sea. And because tonight is the Passover of the Lord, we know that no darkness is dark enough, no death sharp enough, to separate us from God.

Almost exactly 75 years ago, American forces liberated the concentration camp at Dachau. The prisoner Gleb Alexandrovich Rahr, an Orthodox Christian, described what happened a few days later: Greek and Serbian clergy who had been prisoners, wearing vestments made of towels over their striped camp uniforms, led the Great Easter Vigil service, singing the chants and reciting the texts entirely from memory. In the midst of unimaginable death and horror, hell was harrowed and the Resurrection proclaimed.

Every time the church conducts a funeral, we use another set of hallowed words from the Eastern church: and weeping o’er the grave, we make our song.

Perhaps this year it’s not so much making our song as literally standing up, with the tears still running down our faces, and spitting in the face of death.

And now my mother and I are both going to cry, because the only way I can think of to end this meditation is with her translation of the old English poem Piers Plowman, in the climactic scene where Jesus faces down the devil at the gates of hell:

The bitterness that you brewed, now brook it yourself!

You doctor of death, drink what you made!

For I that am Lord of life, love is my drink;

And for that drink today I died upon earth. …

Then shall I come as a King, crowned with angels,

And have out of hell all human souls.

We may be in the dark, in the tomb, in hell. But Jesus is here, and he is risen. We don’t have to wait for the sun to rise tomorrow, or for an Easter morning service in the church building, or for the end of the pandemic: Christ is risen, right now.

Amen.

This is really wonderful. Thank you!