All Saints’, Dorval

August 2, 2020

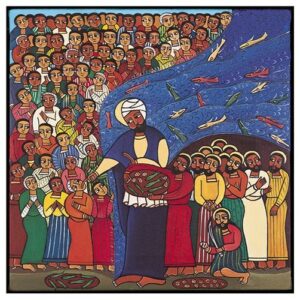

Then he ordered the crowds to sit down on the grass. Taking the five loaves and the two fish, he looked up to heaven, and blessed and broke the loaves, and gave them to the disciples, and the disciples gave them to the crowds.

This sentence is often cited as the original source for the “fourfold action” of the Eucharist – taking, blessing, breaking, and giving. The same four verbs are repeated in Matthew’s account of the Last Supper, when Jesus institutes the Eucharist. Whole long books have been written analyzing this structure and reflecting on how it applies to our celebration of the Eucharist as a church.

And yet, here we are in a time in which we have not been able to gather for Communion for almost five months. How do we engage with the well-known, well-loved story of the Feeding of the 5000, at a time when its clearest parallel is denied us?

Perhaps the removal of that parallel gives us the opportunity to find other meanings in this story that we might miss if we simply focus on the bread, and on the fourfold action, the taking, blessing, breaking and giving.

For example, the passage begins with “Now when Jesus heard this.” What had he heard? The death of John the Baptist. The Feeding of the 5000 begins with Jesus taking a boat to a “deserted place” to try to get away alone and work through his grief over the death of a man who had been, among other things, his cousin, friend, and mentor.

But the crowds beat him there, and when he arrives he finds not solitude, but a needy and clamouring crowd. Despite his exhaustion, he has compassion for them and cures those who are sick, and when it starts to get dark, the disciples bring up the question of how to feed all these people.

There is much here to reflect on, about grief, and boundaries, and the need for solitude and prayer, and what it feels like to have and to offer compassion at the same time that one is in need of compassion oneself. Not irrelevant, perhaps, to life as the pandemic drags on and on, and some of us are increasingly lonely while others are thoroughly sick of the presence of their nearest and dearest, and all of us are much more limited than usual in terms of being able to seek out a change of scene.

Grief is all around us, and new and strange demands are being placed on our capacity for compassion: many of our impulses to help those we know and love are thwarted by social distancing, while the anguish of complete strangers continues to thrust itself before our eyes on our computer and television screens. We could do much worse than to follow Jesus’ example and seek out time for prayer and space for solitude with God – even if it takes a while to extract ourselves from the pressure of daily life to achieve that time and space! And we could do worse than to lean into our impulse for compassion, even when the need seems overwhelming and the response impossible.

One of the perennial controversies about the story of the Feeding of the 5000 (which, of course, was really more like the Feeding of the 15 or 20,000) is the nature of the miracle that occurred – was it really Jesus multiplying the bread and fish, in defiance of the laws of physics? Or was the real “miracle” that people’s stubborn, selfish hearts were softened and opened and they were moved to bring out the food that they were hiding and share it with each other?

I tend to favour the former option, for a number of reasons, among them that once you acknowledge the possibility that God’s own Self became incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth, it hardly seems like a stretch to assume that he could break his own rules if he wanted to. But regardless of which interpretation you choose, this story is clearly about the overflowing love of God overcoming all our human concerns about scarcity and lack. And in normal times, the Church represents this love by welcoming all to the baptismal font and Eucharistic table.

But it will be at least a couple more months before we gather around the Eucharistic table. God’s overflowing love, however, knows no limits or boundaries, and so while we wait, we turn to the other half of the traditional worship service – the Word.

If there has been a blessing in this enforced fast from Communion, it has been in the opportunity to go deeper in our engagement with Scripture. Our worship is now focused around the Word. Six days a week, our Evening Prayer group is praying together through two books of the Bible at a time. The newest awakening of the world and the church to the systemic sin of racism has encouraged us to seek out other voices and learn from their readings of Scripture, to understand how these stories are heard by ears other than ours, filtered through experiences very different from ours.

We are, in fact, wrestling with God through Scripture, just as Jacob wrestled with God at the ford of the Jabbok. And we will not let go until we receive a blessing, even if it is not in the form of bread and wine we are accustomed to. Jacob was renamed “Israel” for his willingness to get in there and duke it out with God, one on one: “for you have striven with God and with humans, and have prevailed.”

The abundance of God’s Word is matched only by the abundance of God’s table, and the more voices are included in the conversation, the richer it is. In this regard, our conversation about Scripture is rather like the interpretation of the Feeding of the 5000 that posits that everyone had food hidden in their bags but were afraid to bring it out: once the first person has the courage to offer a part of their story that connects to God’s story, the next person is encouraged and empowered to do so as well, and all of our hearts and understandings are expanded as we wrestle with God in community.

The other day, as Peter and I continued our quarantine, the Lekxes – Rebecca and the other Peter – dropped off a pan of cinnamon rolls on our doorstep completely out of the blue. The next morning, we had some for breakfast, with scrambled eggs and strawberries (the strawberries had also been dropped off, at our request, by Carolyn Hill). If we weren’t in isolation, but had been eating with others, they might have provided bacon, hashbrowns, and any number of additional breakfast treats.

God multiplies the loaves and fishes, and provides the nourishment of God’s word. But the meal is made richer by each of us bringing our own unique perspective.

Someday, and God willing may it be soon, we will gather again around a real table, both to take, bless, break and share the bread and wine, and to have fellowship over a good church potluck again. But in the meantime, we have the rich feast of God’s word to explore, and each of us is welcome to add our voice, share our story, urge each other to understanding and compassion, and wrestle with God until we obtain a blessing.

Amen.

Leave a Reply