All Saints’, Dorval

September 20, 2020

The Parable of the Vineyard is one of those stories that’s a touchpoint for me; it keeps coming up in different contexts, and has become central to how I think about God.

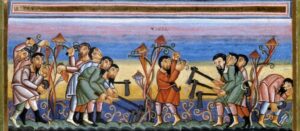

A retelling and reinterpretation of this parable is a key portion of the medieval poem on which I wrote my undergraduate thesis, so I spent over a year of my life living intimately with it from a literary perspective.

A paraphrase of part of this parable also forms the climax of the Easter Proclamation of St. John Chrysostom, which you heard my father read at our Zoom Easter Vigil back in April if you attended that service.

And it’s probably not coincidental that my mother, my first and most influential theologian, also regards this parable as an important piece of evidence for her claim that God’s most central message to us is “there is enough and more than enough” – a phrase you have heard me repeat many times if you’ve been there when I told Messy Church stories.

The traditional interpretation of the Parable of the Vineyard is simple: that no matter how long you have been a follower of Jesus, you are no more and no less a citizen of the Kingdom of God. Having worked longer and harder than others doesn’t mean you get to go to some sort of extra-special, higher-level heaven; as long as you’re in, you’re in, and God loves and rewards all God’s children equally.

In recent years, there has been a strong trend toward reinterpreting many parts of the Bible through the lens of structural oppression and power dynamics. Scholars and theologians have looked at the actual economic and social realities of Jesus’ time and how those factors affect his message, and asked how that message can be claimed by marginalized groups of today.

In general, I think this is an important and valuable endeavour. But when I turned to one of my regular commentary sources this week, I found a reading devoid of Good News – claiming that the landowner was a grasping union-buster who was exploiting the workers and revealing their powerlessness (how that squared with paying some of them twelve times what they were expecting to get, I’m not at all clear).

In this case, though, I think it’s possible to have our cake, interpretively speaking, and eat it too. We can take this parable as a paradigm of “enough and more than enough”, of the idea that we are all uniquely and infinitely valuable to God entirely separate from how much we work or what we produce, and we can use that lens to look at what that would look like in a real-world, economic context.

Because God knows the world is asking these questions these days. When huge swaths of the economy shut down in March, we were all forced to reckon with the fact that suddenly, going about our daily business – including working and shopping for necessities – had become a life-and-death endeavour for much of the world’s population. And that for some period of time, a lot of people were not going to be able to be as economically productive as they had previously been, while still needing necessities like food and shelter.

My home country has, not surprisingly, dealt with these questions with a particularly stubborn insistence on cruelty and refusal to acknowledge the government’s obligation to provide for its people’s basic needs; but even in Canada, there have been complaints about people “freeloading” off the CERB programme and using it as an excuse to not work, as though not being forced to take any job available in order to keep food on the table was somehow an indicator of moral turpitude. It’s as though we have become unable to see our fellow human beings as anything other than economic units, either to produce things for us, or to buy what we produce, or as competition in some kind of game where if anyone ever gets anything they don’t “deserve”, everyone else loses.

Jesus, and this story, are here to remind us that if we’re talking about “deserving” between humans and God, that none of us “deserve” anything whatsoever; that all of it is pure gift, pure grace. And that if we are to belong to the Kingdom of Heaven, that is how we must see our fellow humans as well: as “deserving” not a carefully tabulated accounting of exactly how much we owe each other, but rather of everything we need to flourish.

One interesting side effect of the pandemic is that remote work opportunities, which disabled people had been asking for for years, suddenly became widely available because there was no other option. Imagine how much talent and energy could have been unleashed years earlier if managers had had a little bit more imagination and rather than insisting on treating everyone the same, had been willing to figure out how to allow them to contribute equally.

In early May, the bishops of the Anglican Church of Canada wrote an open letter to the government expressing support for a Guaranteed Basic Income, as an expression of our faith and our commitment to care for each other, and especially the most vulnerable. It is now, we understand, being seriously considered. And a GBI is basically exactly what this parable proposes – giving everyone “the usual daily wage”, enough to sustain life, whether they worked for twelve hours or for sixty minutes.

Predictably, the workers who did put in a whole day’s labour are disbelieving and resentful when those who came late are given a day’s pay rather than only a fraction. So often, people who have suffered in pursuit of a goal feel that they have “earned” it and that no one who has put in less effort should be able to get the same results. Women who had inadequate maternity leave a generation or two ago are scornful of those who get a full year today. People who had to take out loans to pay for college get angry at the proposal that education be made more affordable because “I had to do it; why can’t you?” It is a hazing mindset, that perpetuates abuse and trauma for no other reason than people resenting others for having an easier time than they had – a zero-sum mindset which, if carried to its logical conclusion, would result in nothing ever improving for the human race in any way whatsoever.

And so, in the Kingdom of God, our deep conviction must be that, in fact, there is enough and more than enough; that your joy and flourishing does not detract from mine, but rather adds to it; that all of us simultaneously are owed nothing and yet deserve everything; and that God’s will for us is not a brutal struggle for survival, but abundance and delight beyond imagining.

As Chrysostom’s Easter proclamation puts it:

All who have laboured from the first hour, let them today receive their just reward.

Those who have come at the third hour, with thanksgiving let them keep the feast.

Those who have arrived at the sixth hour, let them have no misgivings; for they shall suffer no loss.

Those who have delayed until the ninth hour, let them draw near without hesitation.

Those who have arrived even at the eleventh hour, let them not fear on account of their delay.

For the Lord is gracious, and receives the last even as the first; he gives rest to the one who comes at the eleventh hour, just as to the one who has laboured from the first. He has mercy upon the last, and cares for the first; to the one he is just, and to the other he is gracious. He both honours the work, and praises the intention.

Enter all of you, therefore, into the joy of our Lord, and whether first or last, receive your reward. O rich and poor, one with another, dance for joy! O you zealous and you negligent, celebrate the Day! You that have fasted, and you that have disregarded the fast, rejoice today! The table is rich-laden, feast royally, all of you! The calf is fatted, let no one go forth hungry!

As it is in heaven, so may it be on earth.

Amen.

Leave a Reply