All Saints, Dorval

December 20, 2020

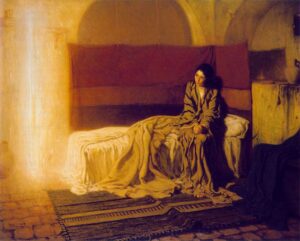

Henry Ossawa Tanner, “Annunciation”

The readings this week seem to be all over the map. First we hear of King David’s plans to build a temple for God in Jerusalem, which God himself thwarts, telling David that instead, God will build him a house, in the form of a neverending line of descendants. Then we hear the very last three verses of the letter to the Romans, which don’t even quite form a complete sentence, and which seem to have been chosen for this Sunday simply because they refer to the prophetic writings making known God’s revelation to the Gentiles.

And then, finally, we hear the familiar story of the Annunciation, of the angel Gabriel appearing to Mary and her consent to be the mother of Emmanuel, God with us. The angel tells her that her child “will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his ancestor David.” This, of course, provides the connection back to the reading from Samuel, which foretold David’s unending line.

Is there any more substantial theme, thought, which can provide a thread of connection among these readings for this, the Fourth Sunday of Advent?

John Frederick, the scholar who wrote this week’s commentary on the passage from Romans, certainly drew a short straw when it came to content! But he nevertheless wrote an interesting and quite profound meditation on the concept of glory. When Paul concludes his Epistle by writing, “to the only wise God, through Jesus Christ, to whom be the glory forever!” he is not just closing his letter with a platitude – he is wrapping up a theme that has been central through the sixteen chapters of Romans, “the project of bringing all humanity to the obedience of faith in the Gospel in order to bring great glory to God.”

As Frederick points out, it might seem rather crass of God to demand that we give glory to God. After all, if God is infinite and all-powerful and so on, why does God need glory from us?

But this begs the question of what we mean by glory. And here, the story of King David and the question of whether he will build the temple, comes into sharp focus. David wants to build the temple to glorify God – and, presumably, on some level, to glorify himself, to cement his status as a powerful king who can command the resources to build a magnificent stone building full of sculpture and gold leaf and fine linen. But God has other ideas. For God, what will give glory – both to God and to David – is to demonstrate God’s power by providing David with an unbroken line to follow him on the throne.

And even that heritage of Davidic kingship does not meet the standards of human glory. Because Mary, after all, is not sitting in a throne room or a queen’s boudoir when the angel comes to her. The Davidic kings have, in fact, been out of power for centuries by the time that Jesus is born. Jesus’ descent from the house of David does not mean he succeeds to any earthly power or prestige. And yet God is glorified in him, not in power, but in self-giving love.

Frederick writes, “The humility of God in the person of Jesus Christ redefines glory forever. The posh royal thrones of human rulers no longer express the glory of true kingship. The royal throne of the crucified God is now forever defined by the humility of a carpenter on a cross.”

True glory is found not in pomp and arrogance, but in creation, in love, in justice, in peace.

If there’s anything we have learned in the last nine months living with the coronavirus pandemic, it’s the transience and eventual meaninglessness of the trappings of earthly glory. The preoccupation with the rich and famous that might have seemed merely vapid before COVID-19, is now revealed as actively harmful. We watch the fortune of Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon.com, balloon into the hundreds of millions as he profits from the current situation; some might see that as the glory of someone become the richest person in history, but the scriptures would teach us otherwise.

If we’re looking for people worthy of glory, perhaps we could turn to José Andrés, the Spanish chef whose charity, World Central Kitchen, has fed hundreds of millions of people worldwide in the aftermath of natural disasters, and which has been tackling the hunger crisis in the US in the face of its inadequate government response to the economic devastation of COVID. Or, indeed, we could turn to Jeff Bezos’ own ex-wife, MacKenzie Scott, who, upon securing access to a quarter of his fortune in the divorce, has given a staggering $6.9 BILLION away in less than as many months, focusing on the neediest and most underserved communities.

But glory doesn’t even necessarily rely on proximity to celebrity. Again, the pandemic has brought that into sharp focus, revealing that the “essential workers” of this world are the folks who stock supermarket shelves and clean hospital rooms, not the ones who sit atop the financial markets. In addition to enormous suffering and grief, COVID has brought to light a thousand instances of anonymous selflessness and love.

And it has also taught us that some of the most mundane things are also the most glorious, especially when you can’t have them for a while. A hug with someone you love, but don’t see often. The experience of making music together. A visit to a new and beautiful place – or an old and familiar one.

But it’s also been glory that gets us through. The glory of the sunrise, of a glimpse of a rare bird, or – as I’ve been following avidly this week – the formation of the ice on the St. Lawrence. The first cup of coffee, or a beloved recipe, or a familiar walk, or the love of someone who shares your household. What would we do without these little daily glories?

Jesus came, not in power and majesty, but into this same humble, daily world that we all occupy.

In seminary, I read a remarkable text called the Heliand, also known as the Saxon Gospel, a retelling of the story of Jesus for the peoples of northern Europe as they were being converted to Christianity in the ninth century. It takes some notable liberties with the story in adapting it to the fierce northern tribes, and the one that I particularly remember is that at the Nativity, Jesus is described as being swaddled in silk and jewels, as befitted a king.

Which, of course, completely undercuts the whole point of the original story, which is that God’s glory is not defined by shiny external trappings, but rather by love – love which is expressed precisely by coming among us in a way that did not befit a king.

Mary listens gravely to the angel as Gabriel tells her that she is the favoured one of God, and immediately following this experience she sings a song of reversal and revolution, proclaiming that the lowly will be lifted up while the proud will be scattered.

So yes, we give God glory. But then God turns around and gives that glory right back to us, in the form of God’s own self, dwelling within a young woman from Nazareth, and dwelling with, and within, us all, in daily blessing, and in humble and self-giving love.

Amen.

Leave a Reply