All Saints, Dorval

January 3, 2021

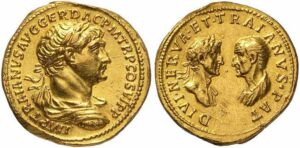

Roman aureus (gold coin) struck under Emperor Trajan, showing the Emperor and both his biological and adoptive fathers.

Please note: I waited too long to post this sermon and am unable to reconstruct the portions that I added extemporaneously toward the end. My apologies, and hopefully the gist comes through!

Then the Creator of all things gave me a command, and my Creator chose the place for my tent. He said, “Make your dwelling in Jacob, and in Israel receive your inheritance.”

He destined us for adoption as his children through Jesus Christ, according to the good pleasure of his will … this is the pledge of our inheritance toward redemption as God’s own people …

On this second Sunday of Christmas, this theme of adoption and inheritance really jumps out from our readings.

What comes to mind when you hear the word “adoption”?

Perhaps you think of a friend or family member who is adopted – or perhaps of someone you know who is a birth parent. These thoughts could be filled with great joy, or deep sorrow, or both.

In our lifetimes, the way that western societies approach adoption has changed radically. Not very many decades ago, adoption was often veiled in shame and secrecy. Children who were adopted were never told the truth, or if they were told, it was not until they were older and they were then discouraged from asking questions about their birth family or thinking of their adoptive parents as anything other than their “real” parents. People who gave birth to children whom they decided to – or were forced to – place for adoption, had no idea what had happened to those children, as all formal adoption records were “closed” with the identities of those involved kept secret.

Today, the pendulum is moving much more in the direction of openness and ongoing contact between birth parents and adoptive parents. Children are told that they are adopted early on, so that they can’t remember a time when they didn’t know. And when birth parents are able to, they are encouraged to play an active role in the children’s lives. But adoption is still a complex topic freighted with many emotions, and it inevitably holds at its heart the rupture of a previous family bond.

Interestingly, the original audience for these scriptures would have understood adoption very differently. The early Christians, and their Jewish contemporaries, were a part of the Greco-Roman world, and in that context, adoption was often something that happened between adults, for economic or political purposes. If a powerful man had no obvious heir among his family, to take over his business or estate, he would simply identify and adopt someone with the necessary skills. Adoption of children also happened, but was much less formalized, and usually took place within different branches of the same family.

In fact, for almost a century starting in 96 AD, the imperial succession took place via adult adoption, leading to the most enduring era of peace and good government in all of Roman history – which ended only with Marcus Aurelius’ major lapse in judgment of allowing himself to be succeeded by his biological son, Commodus, rather than by a hand-picked adopted heir. And Commodus, predictably enough, was a disaster.

So what happens when we map these very different understandings of adoption onto our scriptures for today?

For their original audiences, the idea of being adopted by God would have carried a connotation of being chosen, worthy, and empowered. For them, adoption was something that happened when a powerful (and often wealthy) person, someone who had privileges and resources to bestow, took an interest in you and decided that you could be of use to them in carrying out their goals.

In the Christian context, God would adopt you because of your faith, in order to carry out God’s goal of salvation for the greatest number of God’s human children. The mechanism for this adoption was, of course, baptism. Jesus, the God incarnate, would thus be (as Paul describes him in Romans) “the first-born of a large family”, with all the younger siblings modeling themselves on him.

After such an adoption, you would still be acknowledged as a part of your original family, but your new loyalties and role would generally take precedence over the former ones.

Today, on the other hand, adoption usually means being grafted into a new family right at the beginning – as a baby or a young child – though of course older children are sometimes adopted. One adult adopting another is almost unheard of (except in some examples from before widespread civil rights for LGBTQ+ people, when one partner would adopt the other in order to secure at least some legal rights as a family).

And it certainly serves, as a metaphor, to remind us that God does not choose and adopt us solely because we have gifts and talents that can be put to use in God’s service – although we do! – but rather that we are adopted simply and solely because of who we are, because God made us, and delights in us, and considers us beloved, entirely apart from anything we can do or become.

When John takes up this theme in the prologue to his gospel, he puts a different twist on it: “But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God.” Here, John seems to be denigrating physical birth, with its inevitable biological messiness, in comparison to the relative tidiness of spiritual adoption. I’m not sure that’s a dichotomy that we want to push too far – especially in the season that celebrates precisely the fact that God was born via that very process, in all its blood and mess and fleshiness, even if “the will of man” was not involved. Each of us is, after all, born that way, even if we are later reborn, or adopted, through the waters of baptism.

And with adoption comes another image: inheritance. Something which we perhaps associate most with mysteries or other kinds of fiction – the murder victim being killed for their wealth, or the long-lost uncle leaving a legacy that changes the protagonist’s life. But of course God’s inheritance is not something that relies on someone being dead to be passed on to us. It is something that we can claim immediately, and that can never be taken away.

In Sirach, when God gives Wisdom her “inheritance,” it seems to mean “a dwelling place, a settlement, a place to belong.” In Ephesians, the inheritance is our part in the salvation accomplished by Jesus, the “redemption as God’s own people.”

In other words, this inheritance is far more than the kind represented by account numbers, stock certificates, or real estate – or even about specific heirlooms, however precious and meaningful. This inheritance is about belonging and being beloved. We belong to God forever, and we are beloved by God.

So, as this Christmas season draws to a close, as we celebrate God’s birth into the human family and our own adoption into the divine family, perhaps the question we should be asking ourselves is – what difference does it make? How does it change my life, that I am beloved by God, that I belong to God, and have done so since birth? What would be different for me, if it were not the case that God had chosen me, given me a task to do and the gifts and faith to accomplish it?

Jesus, Emmanuel, God with us, is the first-born among a large family. We all, by virtue of our baptism, are siblings in Christ, called, chosen, and beloved. In this Christmas season, and always, may we live this truth, claiming our inheritance as God’s children.

Amen.

Leave a Reply