All Saints, Dorval

February 14, 2021

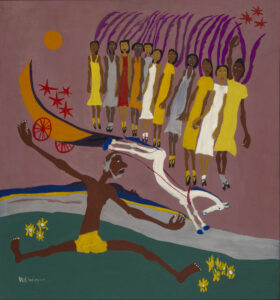

William H. Johnson, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” 1944

Today is the Last Sunday after Epiphany, known informally as “Transfiguration Sunday” because the story of Jesus’ transfiguration on the mountaintop is always the gospel reading for the day. It is also the day that we’ve chosen this year at All Saints’ to particularly observe Black History Month.

That’s a lot of thematic weight for one sermon to carry! But there are real connections between the two observances; as you noticed if you saw the remarkable image that Jennifer found to accompany the first reading, the famous African-American spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is a reference to the chariot of fire and horses of fire that carry Elijah away to heaven in that passage from the book of Kings.

On Thursday night, I convened on Zoom a group of folks to discuss these readings in the light of Black History Month. It was a terrific conversation, and there’s no way I can cram all the insights that were shared into one sermon! But you should know that what I say this morning must be credited to them, and not just to me.

It is appropriate that we conclude the season of Epiphany with the Transfiguration, because it is itself an epiphany, a manifestation, a revealing or unveiling (as the Epistle hints). And in the past year, and the past decade, North American society has experienced its own unveiling and manifestation when it comes to the structural racism that has been simmering in our society for half a millennium. This was not, of course, a surprise to the people of colour experiencing the racism; but those of us whose skin colour puts us in the privileged category, have learned a great deal and have a great deal more to learn.

A couple of weeks ago, a self-identified young Black queer priest in the Church of England, Jarel Robinson-Brown, dared to name white nationalism in the UK in a post on Twitter. His truth-telling was rewarded with an avalanche of homophobic and racist abuse, including death threats (thus, of course, proving his point many times over), and the institutional response from his bishop and diocese were sadly lacking. If the truth cannot be named in the Church, of all places, we are failing the Gospel we claim to live by, and failing the vulnerable and marginalized among us.

As Jesus’ true self is revealed to his followers on the mountaintop, so we must be ready to receive and respect each other’s true selves, to hear each other’s stories, in order for real understanding and reconciliation to take place. For centuries, Black people and other people of colour have had to hide their true feelings and the reality of their lives and experiences, in order to survive in a society that oppressed them and then denied that oppression. The first step in ending this sick dynamic is making space for everyone’s truths to be shared and heard.

On the mountaintop, Jesus is joined by Elijah and Moses, representing (among other things) the law and the prophets. Building on this foundation, Jesus calls his followers to live by the law of love, and to live into the prophetic future of love. We are called, first and foremost, to love each other actively and generously, which includes changing the unjust structures of society that prevent some from reaching their full potential flourishing.

One connection between the story of Elijah and that of Jesus – besides the obvious, of God speaking from heaven and followers seeing miraculous sights – is that both focus on the transmission of authority, on passing the torch, so to speak. And both do this in relationships where parent-child language is used.

Elisha asks Elijah to inherit a double share of his spirit. A double share of the inheritance is traditionally the portion of the eldest son. And, of course, as Elijah is being taken up from his, Elisha cries out, “Father, father! The chariots of Israel and its horsemen!”

And Jesus on the mountain top, in turn, hears an echo of the words that were spoken at his baptism. In the Jordan, God says, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.” At the Transfiguration, God says, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!” At the baptism, Jesus’ identity is affirmed directly to him; on the mountaintop, his followers are told to listen to him, creating a direct chain of influence from God the Father, to Jesus the Son, to his followers.

Such ancestral and prophetic heritages and legacies are tremendously important in many communities of colour. And in many ways, the current moment feels like a passing of the torch in the ongoing struggle for the lives and civil rights of Black people.

Growing up in New England in the 1980s and 90s, we were taught about the abolition and civil rights movements in ways that were basically accurate, but very much gave the impression that the problem was solved. I sang “We Shall Overcome” at school concerts in honour of Martin Luther King Day, but was largely oblivious to the ways that structural oppression continued to deform the lives of my Black classmates and friends.

Then came the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, and the Black Lives Matter movement that arose as a result, and started to shake white America out of its complacency. Soon, I found myself at a demonstration singing “We Shall Overcome,” not as a concert piece or a historical artifact, but as a living song of protest – and it was surprisingly powerful. The truth was being revealed; the torch was being passed.

A new generation is assuming the inheritance of its elders and the mantle of leadership, carrying on and building on the work done by the former generations. Both the Elijahs and the Elishas are essential to the work. The Elijahs deserve to be honoured and imitated. The Elishas deserve to be supported and respected, even if their ideas and goals seem to go beyond what the Elijahs could have imagined or dreamed of.

On Thursday, I got the news that an old friend of our family, a college classmate of my mother’s, had died suddenly in a car accident. Lydia was also a priest, among the first generation of women to be ordained in the Episcopal Church. I have many colleagues of my own generation who generously praised her mentoring and support of younger clergy: people of colour, LGBTQ+, and others who had to fight hard to be included and heard in the power structure of the institutional church.

As one of the first to break the stained glass ceiling, Lydia could have rested on her laurels. Instead, she chose to welcome and help those who were still excluded, thus making room for their voices, their truths, and their leadership. Those who break new ground must be continually extending their hands to those who come behind them, saying, “These are my children, the Beloveds; listen to them!”

On the mountaintop, law and prophecy join, and are united in love. In that same revolutionary love, let us hear and understand each other’s truths, and go forward into a new day of justice, led by a new generation.

Amen.

Leave a Reply