All Saints’, Dorval

July 18, 2021

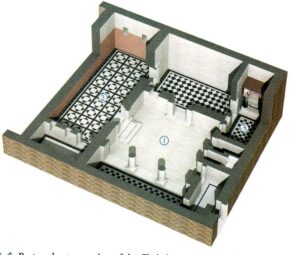

Reconstruction of the house church at Dura-Europos.

So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are citizens with the saints and also members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone. In him the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord; in whom you also are built together spiritually into a dwelling place for God.

Today is my last Sunday preaching and officiating before my annual vacation, which I’m taking this year in a single four-week chunk. When I come back, we will – God willing – be moving full speed ahead toward our planned reopening on September 12, which will include cleaning up the various messes that have accumulated in the church building during a year and a half of not being used regularly for Sunday morning worship, and welcoming a live congregation back to a sanctuary that looks familiar and yet different, with a new and surprisingly spiffy-looking vertical lift, and all the technology for long-term Zoom access to services for those who can’t be there in person. The COVID-19 pandemic has rearranged our priorities, sped up some processes, and slowed or halted others.

Right before the virus hit, we had held the first meeting of the Building Projects Committee, which was charged with looking at our physical plant holistically, and trying to prioritize and coordinate the changes desired by various members and groups in the congregation, so that we didn’t end up ripping out half of Project A in order to achieve our goals on Project B.

As we return to the use and consideration of our buildings, we’re realizing that people have had a lot of feelings about missing them over the past year and a half, and that there are assumptions and expectations about how they’re used that it would be helpful to “surface”, as the corporate jargonists say, before we make any big decisions.

Our readings today invite us to consider the meanings and uses of sacred space, and what our priorities should be as we contemplate how to live in it and how to change it.

David wants to express his own power and his faith in Israel’s God by building God “a house of cedar” – in other words, a temple as formal and beautiful as David’s own royal palace. A noble and worthy endeavour, but God, for God’s own reasons, tells David that he is not the one to carry it out. God points out that God has been able to protect and bless the people just fine while the ark of the covenant has been carried around and set up in temporary dwellings, tents and tabernacles. God’s priorities at this point are ensuring good leadership and safety from enemies, and God promises that God will build a house for David – will ensure the continuation of his royal line – and it will be David’s son who finally builds the splendid temple.

Ephesians, meanwhile, in the passage I quoted at the beginning of the sermon, emphasizes that God’s people themselves are a temple, “built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone,” and that both Jews and Gentiles are united in this new building, in which God dwells directly, without needing to be worshiped in a particular place.

Passages like these have sometimes been used to support arguments that the church shouldn’t have buildings at all, that we should be a people on the move, “tenting” in various places like the Israelites in the desert.

And it’s true that outdated, overlarge, badly maintained buildings can be an albatross around a congregation’s neck and can eat up resources that would be better used on ministry. But I don’t think that “get rid of all the buildings!” is the right answer either. There are a lot of things you can’t do when you’re meeting in someone’s living room or in a rented space.

We just sang a hymn illustrated by an image from the frescoes at Dura-Europos in Syria, where a private house was converted in the early third century into a building intended specifically for use as a Christian worship space. Followers of Jesus have always built and modified their physical spaces to make them work for the purposes of worship, fellowship, learning, and service.

Conversely, though, it’s important to realize that we have almost two thousand years of the history of these buildings, and they have by no means always looked the same. Most of us probably came of age in a time when “church” meant pews facing forward, with clergy and other “important” people in robes up front, and everyone else sitting still and quietly (including children, who may have been threatened with a spanking at home if they didn’t behave) and listening to the service, joining in only occasionally in the hymns and prayers.

The church at Dura-Europos, though, had at least two separate rooms, one of which was a very elaborate baptistry where people were baptized by immersion. The location of the actual altar has not been identified; it may have been a moveable table, long since lost to time.

In subsequent centuries, as Christianity became legalized and then the official religion of the Roman Empire and its European successor states, churches became larger and more public. They were built on the model of the Roman basilica or assembly hall, with room for processions and for different configurations. Chairs and reading stands were moveable, and often arranged in lines facing each other or in circles around the font, altar or lectern, so that the words and gestures of worship would be visible and audible to all.

In the Middle Ages, churches from tiny country parishes to great cathedrals had no seating at all; people stood, milled around, or sat on the floor. As worship increasingly became a spectator event rather than something in which everyone participated, chancel spaces were increasingly walled or screened off so that the clergy could focus on the sacred ritual without distraction from the noisy crowd in the nave, not all of whom were particularly invested in the service; even the more devout would often read aloud from their private prayer books while the mass was taking place, since they couldn’t understand the Latin anyway.

It was only with the Reformation, and the emphasis on the preaching of the Word, that the church building as we know it took shape: pews, a prominent pulpit, and the expectation that worship would be quiet and decorous.

As you can see from this whistle-stop tour through almost two millennia of church architecture, the way a building is built determines how it is used, and vice versa. As my seminary church architecture professor put it, “The building will always win.” There are things you can do in a huge cathedral that you can’t do in a little country church – and vice versa. If you want to do something different in the space, you need to change the space.

So, harking back to my sermon from last week – do we want to be a church that dances? And if so, is our current configuration really conducive to that?

Our Gospel reading this morning is two brief snippets from the sixth chapter of Mark in which Jesus and his disciples interact (and escape from!) the crowds. What is left out of the middle, though, are the two stories of Jesus feeding the five thousand and stilling the storm on the sea of Galilee. In feeding the five thousand, Jesus takes, blesses, breaks, and shares the bread, and all are fed.

The liturgical theologian Gordon Lathrop writes of “the broken symbol” in our worship. He argues that there is a natural human tendency to freeze things in place as objects of worship, and try to keep them from changing. This applies to our images of God, to our buildings, to the services that happen in the buildings. But, Lathrop says, God actually models to us the opposite. Jesus breaks the bread, and Jesus’ own body is broken on the cross; and, as Ephesians says, Christ has broken down the dividing wall between peoples.

Every time we start to imagine that something is sacred and untouchable as it is, that is actually a sign that it must be questioned and remade – broken open, so that its symbolic power can be released anew.

And often this entails taking things that have become purely symbolic – like the communion service – and returning them to their roots in the reality of daily life, of sharing a meal together. St. Gregory of Nyssa, the dancing saints church that I talked about last week, serves both coffee hour and their weekly food pantry distribution off of the actual altar, in the sanctuary, stating as powerfully as possible that the sacred meal is not an untouchable symbol, but rooted in the daily, active, giving life of the community.

With Christ as cornerstone, how do we build ourselves into a dwelling place for God, and how do we remake our actual physical space to make that possible? Because that’s the only building project worth doing.

Amen.

Leave a Reply