All Saints’, Dorval

February 6, 2022

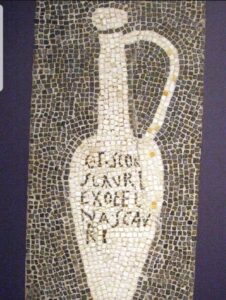

Mosaic from the house of Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, Pompeii, showing an amphora of garum (fish sauce)

***

When they had done this, they caught so many fish that their nets were beginning to break. So they signaled their partners in the other boat to come and help them. And they came and filled both boats, so that they began to sink.

These sentences hit me differently this time around.

Over Christmas, I read a book that threw me into a depressive funk for a good three or four days. The book is called Less is More: How Degrowth will Save the World, by Jason Hickel. Its message is ultimately hopeful, but it spends a lot of time establishing the urgency of the situation that it is responding to, and that’s the depressing part. To put it very simply, human society is in a situation of “overshoot” with respect to the global ecosystem that sustains us. That means that each year, we use more resources than the planet can provide, and create more waste and pollution than it can absorb. And not by a small percentage, but by a significant margin. This is not only ruinous for the environment, but also exacts an appalling cost in human lives, as the resources and labour of people in poor countries are plundered to supply the ever-increasing appetites of the rich.

Hickel demonstrates incisively how what put us in this situation is the global economy’s commitment to an impossible standard of perpetual economic growth. And he offers the prescription of a “steady state” economy, one in which the goal is human well-being and flourishing, not an ideology in which the numbers after the dollar sign must always rise for no justifiable reason.

But if you’ve been thinking gloomily about our current unsustainable situation, in which everything – from oil, to lithium, to soil, to fish, to human lives and labour, are being extracted in huge quantity and fed into the maw of the ever-growing global economy, leaving the earth battered and raw – to hear about Simon and his partners hauling in a catch of fish that nearly sank their boat, can make your stomach drop with dread rather than your heart swell with thankfulness. What happens to the fish stocks in the sea of Galilee, after this giant pile of biomass has been removed from the ecosystem?

It’s easy to dismiss that response by saying “Oh, in the first century the world had orders of magnitude fewer people in it, and the technology level was such that there was no way that they could have the kind of impact on the planet that we have now.” Which is true, absolutely. But it would be wrong to think of Jesus and his followers as existing in some kind of subsistence paradise where at the end of the day everyone ate the fruits of their own toil under their own vine and fig tree.

We think of the fishermen on the sea of Galilee as catching fish which would then be sold at a local market and eaten for dinner within walking distance of where it was caught. But it’s extremely likely that in fact, much of the catch was instead sold wholesale to be processed into garum, or fish sauce.

Garum and other similar products were wildly popular in the Roman world, being added to practically everything to give a dash of funky, fermented, umami flavour. But fish sauce was, of course, not the native cuisine of Palestine; the fish that Peter and his partners caught would be dumped into stone tanks to ferment for a year or more, and then shipped elsewhere, to wealthy population centres where people closer to the powerful elites would consume it. Humanity might have been well within its ecological limits in 30 AD, but the phenomenon of labour and resources being extracted from the poorer hinterlands and transferred to the wealthier centre was already very much a reality. Rome was, after all, an empire, and that’s kind of the entire point of empires.

So what do we do with this story, then? If we can’t take it at face value and straightforwardly rejoice in the abundance, where is the good news here?

First of all, of course, I want to make clear that I don’t actually think that Jesus was contributing to the extinction of fish species or the exploitation of the fishermen of Galilee. Jesus was God, and thus fully in tune with the will of the Creator of the universe. But his actions can certainly invite us to reflect on these things, including those issues that have arisen in the two millennia since he walked among us on earth.

And I think that the crux of the matter lies in the word I just used – abundance. Churchy people hear that word a lot. We have been asked, over the past two or three decades, to cultivate a theology of abundance, as opposed to a theology of scarcity – based on exactly this story and many others like it in scripture. Where God is, we are told – where Jesus is – there is abundance, and therefore we should live as people of abundance, giving generously, and not being afraid of what the future will bring.

Which is true – but possibly not in the way that’s most obvious to us, shaped as we are by the unthinking and impossible assumptions of capitalism. If “abundance” means simply accumulating more and more stuff, without regard to where it comes from or how it affects us to have it, then that is about the furthest thing from the gospel imaginable.

If you’ve listened to any of the stories I tell with the felt board at Messy Church, you’ve heard the phrase, “enough, and more than enough” used as shorthand for the abundance of God’s kingdom. But it only makes sense in the context of the phrase that comes before it – “now we don’t have to be afraid, and we don’t have to fight.”

Abundance is only abundance if it’s abundance for everyone. If no one has to live in fear, and if no one is being violently denied the basic necessities of a dignified life. That is the Kingdom that Jesus has come to bring in.

Jason Hickel concludes his book by emphasizing that even at the current global population of almost eight billion people, a life of security, and dignity, and human flourishing, is possible within the limits of the earth’s ability to sustain us. It just requires a complete overhaul of our economic system, such that we no longer prioritize GDP over actual human health and well-being, and close the yawning gaps between the world’s wealthy and its poor.

We’re so accustomed to equating any kind of limits with scarcity and hardship, that this is very difficult to get our heads around. But think of all the things we could still have as much of as we wanted, even in a world that respected the earth’s limits. Not just intangibles like love and caring, curiosity and creativity, fun and leisure. But all the things that make human life worth living – art and music, sports and nature and learning.

If we removed the intolerable pressure to be always increasing productivity and the bottom line, to be always keeping up with inflation and interest rates and the price of a three-bedroom house – then surely our lives, with our basic human needs met and with the rest of our time filled with all these good things instead, would be infinitely better than they are now? And surely that would look remarkably like the kingdom of God?

In today’s story, Jesus walks and teaches by the lakeshore, and Simon and his partners draw in an enormous, miraculous catch of fish. We don’t find out what happens to those fish – were they fed to the crowds? Shipped off to be made into garum? Left to rot, once the point about Jesus’ power had been made?

But at the end of John’s gospel, after the Resurrection, there is another story that mirrors this one. The disciples are, once again, out fishing, and have had no luck. Jesus (though they don’t immediately know it’s him) appears on the beach, and tells them to lower the nets on the other side of the boat, and they catch so many that they cannot haul in the net.

But this time, the catch is enumerated: one hundred fifty-three large fish. An impressive number – apparently several times the size of a typical catch – but still, not the absurd, unquantifiable haul described in Luke.

And this time, when they bring the catch ashore, Jesus, who has already built a fire on the beach, invites them to eat breakfast. The fish and some bread are cooked and shared. Those who laboured for this food enjoy the fruits of their labour. Friendship is strengthened, souls refreshed, and God encountered, around the fire. There is enough and more than enough – the abundance, not of unthinking consumption based on extraction and exploitation, but of honest labour in harmony with creation and its Creator. Of such is the kingdom of God.

Amen.

Amen