All Saints’, Dorval

February 20, 2022

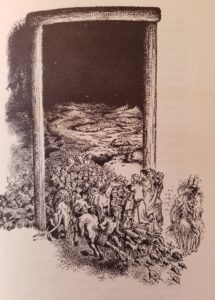

Illustration by Pauline Baynes, from The Last Battle

What do you want your resurrected body to be like?

Maybe you’d like to be six inches taller, or have glorious long red curls, or the kind of eyes that only exist in romance novels. Maybe you’d like to be able to hit a hundred-mile-an-hour fastball, stretch a tenth on the piano keyboard, or land a triple axel – or be able to fly, or breathe underwater.

Or maybe you’d just like to be free of pain that you’ve lived with for months or years.

In C. S. Lewis’ The Last Battle, the culmination of the Narnia Chronicles, when the world ends in Narnia and its people and creatures are invited “farther up and farther in,” into the newly recreated, true and heavenly Narnia, as they make their way up the mountain to Aslan’s dwelling, they find that they can run for hours without tiring, look directly into the sun, and swim straight up waterfalls as easily as though they were taking a dip in a pool.

For some reason, though, I’ve found that many modern Christians are extraordinarily reluctant to claim the bodiliness of our resurrected bodies. From Paul’s hearers in Corinth, to many people I’ve personally had this conversation with, something prevents us from embracing this promise, so amply, lushly, gloriously laid out for us in Scripture.

We don’t know what the people in Corinth objected to about the resurrection of the dead. Maybe they thought it was too earthy, too undignified, not intellectually respectable. Maybe they just thought it was too much to hope for, too good to be true.

But for whatever reason, Paul takes them (metaphorically) by the scruff of the neck and tries to shake some sense into them. And not very gently, either. “Fool!” he rants. “What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. … [Y]ou do not sow the body that is to be, but a bare seed, perhaps of wheat or some other grain. … What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable.”

Modern-day Christians may share these reservations with the Corinthians. Or – and maybe the Corinthians thought this too, who knows – modern Christians may be reluctant to full-throatedly affirm the resurrection of the body because they feel that thereby they deemphasize the importance of recognizing God’s kingdom here on earth, already among us. As the UK charity Christian Aid puts it, trying to counteract the widespread stereotype that Christians are only interested in saving souls – “we believe in life before death.”

Our Gospel passage is, of course, one of the foundational statements of that call to attend to God’s presence right here and now. By loving our enemies, praying for those who curse us, and stopping the cycle of violence, revenge, and greed, we can indeed be part of bringing that Kingdom into being as a present reality.

But, at the risk of sounding like a broken record, this isn’t an either/or. It’s a both/and.

To focus only on the resurrection of the body risks losing ourselves in fantasy – the long red curls, the 100-mph fastball – and forgetting to be concerned with justice and peace right here and right now. But it is equally problematic to focus only on the Kingdom of God here on earth. When we do that, deliberately or not, we give ourselves the idea that it is all up to us, that if we cannot live up to the borderline-impossible ethical standard that Jesus outlines in today’s reading from Luke, we might as well give up, and it will be our fault if God’s Kingdom does not come into being here on earth. (This is not a theoretical objection, either; I have seen it happen, and it can be spiritually deadly.)

In Paul’s time, after all, moral teachers who would challenge their followers with high ethical demands, were a dime a dozen. But only Jesus claimed to have actually defeated death and opened the way to an entire new reality, which is why Paul harps so relentlessly on the subject.

The whole thing only makes any sense at all if God’s Kingdom exists, for real, both here and now, and cosmically and in eternity. In the present and in the world to come. In the already and the not-yet. And thus, our bodies – not just our spirits and souls, but our whole selves, these bodies that are made of the same flesh God created and in which God became incarnate, died, and rose again – are just as immortal as our souls. Where the pie-in-the-sky people went wrong was not in wanting to save souls, but in wanting to save only souls, and forgetting about the bodies.

The earthly Kingdom, like the earthly body, is a seed. It’s good and it’s necessary as a place to start – but when put beside the splendour of the full-grown plant, there’s no comparison. And it is our participation in the heavenly Kingdom, through Jesus’ conquest of death and our baptism into his risen life, that gives us the divine power to do what we can to love our enemies here in this life – because we know that we, through Jesus, have already conquered death, will already live for ever, and thus nothing our enemies can do to us will change that.

The bishop who ordained me, Gene Robinson, was the first openly gay bishop in the Anglican Communion, and you may recall the enormous backlash to his election in 2003. In the following months, he had many occasions on which he was driving to a meeting with a room full of people who were going to say cruel and terrible things to him, and the way he prepared himself to be kind and pastoral to them, was literally to sit there in the car saying, “I’m going to heaven! I can handle this because I’m going to heaven!”

To even speak of a “heavenly Kingdom”, though, is kind of a misnomer, because the Resurrection of the Body does not promise us a new life somewhere else. It promises that God is going to recreate this world, right here, with all the beautiful and wonderful things that we have loved in this life, and with all the wisdom and experience that we have gained from the not-so-wonderful things – but so much greater and more glorious, so much real-er, that the only possible way to compare them is as the beauty of the full-blown rose to the tiny promise of a seed. It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. Flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God – not because they are corrupted and simple, but because they’re simply not strong enough. They must be reborn, like the characters in The Last Battle discovering they can swim straight up the waterfall on the way to Aslan’s mountain.

And maybe this all sounds a little bit exhausting – because, after all, Paul’s entire point is that we can barely begin to imagine the glory that is to come, and it’s too much for our limited mortal senses and capacities. After a long life on earth, even a good and well-lived one, we may just feel tired and want to rest (and there are interpretations of this passage that argue that we will, in fact, rest for a period of time before the Resurrection).

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, characters who were virtuous in life but did not believe in the Messiah, are portrayed as ending up in the best heaven they were capable of envisioning – which, since they were Greeks and Romans, means the dim, tepid paradise of the Elysian Fields, where they walk quietly and discuss philosophy for eternity. And there are days when I can see the appeal of that: when I can see how seductive it would be to just let the seed rest in the dark earth.

But God wants more for us. God wants not only peace and rest, but glory and joy.

So, my friends, dare to hope for the Resurrection of the Body. Dare to believe that our childlike fantasies, our most secret hopes, can actually come true. That we don’t have to restrict our expectations of the world to come, to what’s cautious, adult, rational, dignified.

God’s Kingdom here on earth exists for the sake of the true, eternal Kingdom, the same way that the seed exists for the sake of the full-grown oak tree. And so we, Christ’s followers, dare to believe that what awaits us is not spiritual, abstract, symbolic, but literally, tangibly real.

As Paul goes on, past the point where our reading stopped today:

Listen, I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed. For this perishable body must put on imperishability, and this mortal body must put on immortality. When this perishable body puts on imperishability, and this mortal body puts on immortality, then the saying that is written will be fulfilled: ‘Death has been swallowed up in victory.’

Victory. Glory. Immortality. This promise is for us. For the foolish Corinthians, and for you and me, two thousand years later. It may sound too good to be true. But it is the truest thing that has ever happened.

You are the seed. What will the flower be like?

Amen.

“As the UK charity Christian Aid puts it, trying to counteract the widespread stereotype that Christians are only interested in saving souls – ‘we believe in life before death.'”

We also believe in life after birth …