All Saints’, Dorval

Palm Sunday, Year C

April 10, 2022

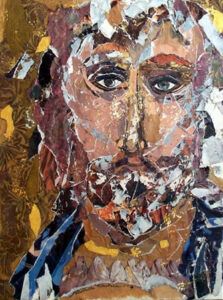

Jesus as the Suffering Servant, by Marcella Paliekara

The Lord God has given me the tongue of a teacher, that I may know how to sustain the weary with a word. Morning by morning he wakens – wakens my ear to listen as those who are taught. … I did not hide my face from insult and spitting. The Lord God helps me; therefore I have not been disgraced …

Thus, from the prophet Isaiah, if you can remember that far back, before the long reading of the Passion according to St. Luke. And thus, from St. Paul, writing once again to Lydia and her Philippians:

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death – even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him …

There is a pattern here. A pattern in which someone in the worst, most degrading circumstances imaginable, someone reduced to the absolute rock bottom of what human experience has to offer, is still, in some essential sense, untouched by that experience, because God is present in the midst of it, and the dignity that God bestows on the individual is inalienable and irreducible.

In Greek, the verb that Paul uses when he says that Jesus “empties himself,” ekenosen, has been taken into English as a noun, kenosis, which means “self-emptying”. Theologians talk about Jesus’ kenosis in his Passion, how through the agony in the garden, the arrest, trial, torture, crucifixion and burial, Jesus emptied himself utterly on our behalf.

Frequently, this then leads to an appeal to us to likewise empty ourselves on behalf of others, following in the footsteps of Jesus. After all, as Jesus said, those who lose their lives for his sake will save them.

We need to be careful here, though. Imitating Jesus, up to and including his kenosis, his self-emptying through suffering and unto death, can be a good and worthy thing. But only if it is something done by the individual’s own free choice, because God is actually calling them to that self-offering. If it’s something inflicted on them by others, it’s just abuse.

In the prophecy from Isaiah, the speaker says that God “has given me the tongue of a teacher, that I may know how to sustain the weary with a word.” God teaches us, if we listen, how to distinguish between the work that we are called to do and the sacrifices we are called to make – even if they are heavy and painful, even if they demand from us everything we have – and, on the other hand, that work that is not ours to do and sacrifices that are not ours to bear. This is the wrestling that Jesus did in the garden of Gethsemane: coming to the realization that yes, this was in fact God’s will, and this was – literally – his cross to bear, and thus he would do so willingly, despite the appalling pain.

God is with us even if we are being abused and tortured, but only we and God can decide what is kenosis and what is meaningless suffering.

On the other side of true kenosis¸ is renewed life. “I know that I shall not be put to shame;” says the servant in Isaiah, “he who vindicates me is near.” “Therefore,” says Paul about Jesus, “God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend.” Even in the midst of it, a self-emptying to which we are called will feel somehow right, even good – even if it comes with pain, fear, frustration, anxiety, sleep deprivation, or other human hardships. And when it is over, when the hard and holy goal has been reached, there is great rejoicing.

I am called to be a priest. Over the last two years of COVID, one of the deeply destabilizing things about doing Holy Week and Easter in lockdown is that it didn’t feel enough like kenosis. Normally, I am physically absolutely spent by the afternoon of Easter Sunday. In 2020 and 2021, I was doing all the services, but I was doing them sitting in a chair in front of a computer. I wasn’t running all over the church building setting things up and putting them away. I wasn’t leading activities for a dozen or more loud and active children. I wasn’t marching up and down Lakeshore waving palms in the snow. I wasn’t singing at top volume until my voice cracked. I wasn’t worshiping and leading with my whole body and self, the way I usually do, and it just felt all wrong.

Perhaps you can think of an experience requiring similar determination and stamina in your own life. Being a teacher, or a health care worker. Walking the floor with a crying baby. Writing a thesis, building a house, planting a garden. Working through grief or trauma in counseling. Driving through the night to transport refugees across a border. Anything worth doing, that stretches us to the utmost of our capabilities. There may be exhaustion, tears, self-doubt. But at the most fundamental level, we know that this is what we are called to do and that God is helping us to give it everything we have.

This Holy Week, Jesus shows us the way of kenosis. And God wakens our ears to listen as those who are taught, showing us which burdens are ours to carry along with our Saviour, and sustaining the weary with a word as we shoulder those burdens, until we, who have shared Christ’s obedience, may come also to share Christ’s exaltation.

Amen.

Leave a Reply