All Saints by the Lake, Dorval

Proper 33, Year C (Remembrance Sunday)

November 13, 2022

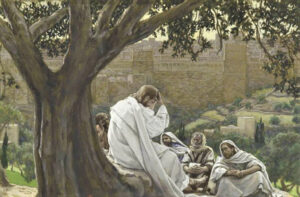

James Tissot, “Prophecy of the Destruction of the Temple,” c. 1890. Brooklyn Museum.

This will give you an opportunity to testify. So make up your minds not to prepare your defence in advance; for I will give you words and a wisdom that none of your opponents will be able to withstand or contradict.

It’s a joke, a cliché, that Anglicans are allergic to anything resembling “testimony.” And I sincerely hope that none of us will actually be handed over to the authorities and forced to risk harm or death if we refuse to renounce our faith. (Though given the way the last few years have gone I’m not going to rule it out.)

But in the baptismal covenant, which we reaffirmed last week and will reaffirm again next week, we promise to “proclaim by word and example the good news of God in Christ.” That sounds like not only testimony but – even more terrifyingly – evangelism, a word that has rightly been given negative associations by the aggressive proselytizing of some groups of Christians.

And Jesus says not to prepare a defence in advance; so maybe we should just not talk about any of it anyway?

It’s true that we probably don’t need to genuinely worry about possible martyrdom – but I think this text does contain a serious invitation even to us Christians who live in (more or less) free, pluralistic societies. Even if we don’t have a speech written down word for word in our back pockets in case we’re hauled before a hostile authority, it is important to define – for ourselves, if for no other reason – what it is we actually believe, what it means to us, and whether we are in fact prepared to die for it.

Three years ago, just before the pandemic, All Saints did a series of Facebook Live interviews with members, in which we asked simple questions about faith like “What is your favourite Bible story?” It was a surprising and delightful opportunity for people to speak about things that were close to their hearts in ways they might not have thought to do before.

But sometimes the stakes are higher. If we are brought before the magistrates (or whatever the twenty-first century equivalent in risk and intensity might be) they’re not going to be interested in the answer to the question, “Why do you go to church?” The question – expressed or implied – is going to be “Why do you follow Jesus of Nazareth,” and “What will you give your life for?”

It’s good to have an elevator pitch for inviting your friends to church, about the beauty of the music, the warmth of the congregation, and the opportunity to give back to the community through charitable activities. But all those things can be found elsewhere. What is it that brings us here, to this place where we read bizarre texts that are thousands of years old, and share bread and wine and call it flesh and blood, and claim that someone who died in 30AD is alive, and talk about death to an extent that makes most 21st-century Canadians nervous?

And if someone held a gun to your head and demanded an answer to that question – would you be able to come up with one?

Hopefully Jesus would in fact give you “words and a wisdom that none of your opponents will be able to withstand or contradict.” But just in case, let’s think a little bit about what really makes Christians unique.

It’s not that we’re particularly moral people. All the world’s major religions agree on some version of the Golden Rule – “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” – and some of them put us to shame with how they live out that commandment; I think in particular of the Sikhs, who feed thousands of people without charge or question every day in their gurdwaras. And you can be an atheist and live an entirely upstanding, righteous life.

What sets Christians apart is not our morality but our beliefs about life and death, time and eternity. We believe, indeed, that God became human in Jesus Christ; that the evil of the world could not tolerate perfect goodness in human form, and put him to death on the cross; but that death likewise could not hold him, and he overcame death for ever, not just on his own behalf, but on ours. And this is why those early disciples who were inspired by Jesus’ words in this gospel passage, were so fearless in the face of persecution and death: because they knew that in their baptism, they had already died in Christ and that God’s new life already belonged to them forever.

And we Christians believe that that promise of new life is not only for us as individuals, but for the whole world, indeed the whole cosmos. Beyond the vision of violent upheaval in today’s Gospel passage, lies the vision of the new Jerusalem in Isaiah, in which God creates new heavens and a new earth, where no sounds of weeping or cries of distress are heard. If we can pass through the agonizing birth pangs of the time in which nation rises against nation, we are promised the joy and security of the new creation, in which no one anymore will labour in vain or bear children for calamity. This is our testimony: that God has defeated death and yearns more than anything to reconcile the whole creation in wholeness and peace.

That is what it all boils down to. That is the creed which, as we stand before the hostile powers of this world, we cannot renounce, because we know it to be true. Christ has triumphed over death for us, and no matter how long it takes, the story has a happy ending.

Most likely, you will never be called upon to suffer and die for this cause (though it would be wise to be ready, just in case). So the question then is – what difference does it make in your life as it is, that you believe this?

Will you proclaim by word and example the good news of God in Christ?

I will, with God’s help.

Amen.

Leave a Reply