All Saints by the Lake, Dorval

December 25, 2022

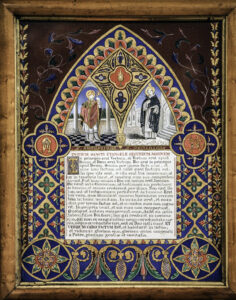

A hand-illuminated text of the Prologue to John. 19th century, Dominican sisters at Stone in Staffordshire.

You know, in fourteen years of ordained ministry, and preaching off and on for a few years before that, I’m not sure I’ve ever actually preached on the Prologue to John before.

It’s known to all church nerds as the ninth lesson in the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols, but the actual Christmas sermons tend to be preached on the even more familiar story from Luke, with the shepherds and the angels.

As is so frequently the case with John, the rolling cadences of his prose are impressive but I find it a bit difficult to actually connect with what he’s saying. What do these beautiful sentences about light and darkness, Being and Word, actually mean for my ordinary human life?

Last night we were bedded down next to some livestock in the straw, amid the pain and mess of birth and the very human sounds of a new baby. Today, we hear of lofty glory, and the letter to the Hebrews chimes in with a meditation on the eternal Son of God, the exact imprint of God’s very being, as much superior to angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs. I wouldn’t blame anyone who felt a bit of scriptural whiplash here.

But of course, the entire point of Christmas is that these two things collide: the glory of God and the reality of human life. John says that the children of God “were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God,” but of course all of us are in fact born in blood and fleshly reality, as John himself acknowledges when he says “the Word became flesh and lived among us”.

At Christmas, we rightly emphasize God’s extraordinary love in coming among us as a human being, subjecting God’s infinite self to the limitations of our existence, learning from the inside what it feels like to be one of us. But the flip side of that approach to the Incarnation is that God becoming human also enables humans to become like God. As in so many other things, our Orthodox siblings here have much to teach us: they consistently emphasize the human becoming divine in response to God’s becoming human.

I confess that sometimes, when presented with the light and glory and perfection of texts like Hebrews and John, I’m not always grateful and enthusiastic. Becoming like God sounds like a lot of work and risk and expectation. A lot of the time I’m more comfortable with a God who comes to sit with me in my chaotic humanity, than with a God who asks me to reborn as a child of the eternal and glorious Word.

In a very similar vein, the prophet Isaiah, in our first reading today, speaks to the exiles from Jerusalem. They have grown pretty comfortable in their lives in Babylon. Returning to the home that most of them have never seen, rebuilding the city, sounds like an awful lot of work and they’re not sure it’s worth it.

But the prophet is relentless. “Listen!” he shouts. “Your sentinels lift up their voices, together they sing for joy; for in plain sight they see the return of the Lord to Zion. Break forth together into singing, you ruins of Jerusalem; for the Lord has comforted his people, he has redeemed Jerusalem.”

And the people did get up, and return to the home that they knew only from the stories of their parents and grandparents, and once more made of Jerusalem the joy of all the earth.

Being born from one state of being into another – whether it’s an ordinary human birth, or God becoming human, or humans being reborn into a divine identity – is always going to come with reluctance and difficulty and pain. But we trust that the end result is worth it.

As many of you know, last Sunday I had just enough time after the Christmas pageant ended to eat a quick pizza at Non Solo Pane before heading down to the Côte-des-Neiges birth centre to attend a birth as a doula. So the Nativity story was particularly on my mind as I observed and assisted in the beautiful, intense, and transformative experience of human birth. And on this occasion (I share this story with permission), I saw something I’d never seen before – when the baby’s head had been delivered but his body was still inside his mother, he opened his little mouth and began to cry! Still in the midst of this enormous transition, not yet fully a separate being from the one giving him birth, he announced his presence to the world.

Because God has become human with us, among us, for us, in Jesus Christ, every human birth partakes of and reflects the wonder of the Incarnation. I imagined baby Jesus doing the same, announcing the accomplishment of the miracle of the birth of God in human flesh, the cry of the half-born baby in the same voice as the Word that spoke Creation into being.

Being born is hard work, and yelling about it in the most intense moments of squeezing and transformation seems like an entirely reasonable response to me. And if the invitation to us is to respond to God’s Incarnation as a human by being reborn from our human existence into the glory of God, I feel like a bit of howling along the way might be entirely warranted.

God, the eternal Word, is born among us at Christmas, trailing clouds of glory, speaking the word of Creation in the voice of a squalling newborn. And God did so in order that we in turn might have the chance to become divine.

A daunting thought, indeed; an invitation we may have to be exhorted, as Isaiah exhorted the exiles, to accept; a process of transformation that may require a few yells of our own to get through.

But the glory is for us. It is not too much for us to claim, to aspire to, to become. God put on human flesh, so that humanity might put on God.

And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth.

Amen.

Leave a Reply