All Saints by the Lake, Dorval

March 19, 2023

“For the LORD does not see as mortals see; they look on the outward appearance, but the LORD looks on the heart.”

It’s really very considerate of the lectionary to give us such appropriate selections from scripture when I wanted to talk about discernment anyway.

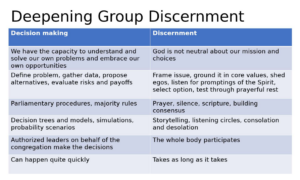

When Heather presents to us by Zoom a week from Tuesday, she will include one slide summarizing a list of differences between decision making – the kind of ordinary work that goes on all over the world to enable families and communities to keep functioning – and discernment – what happens when people of faith work together to listen for, figure out, and try to do the will of God. And it’s really remarkable how many of the elements of discernment are present in the stories we heard read today.

The first item on the list is “God is not neutral about our mission and choices.” There is, in fact, a path that God wants us to be walking, and other paths that are not the right choice for us at this time.

The story of Samuel’s anointing of David as king over Israel begins with God having to say this very clearly to Samuel, who is still stuck in his grief and disappointment about the fall from grace of Saul, the former king. “I have rejected him from being king over Israel,” says God.

And knowing and carrying out God’s will can make life very difficult for the person called to do it. Samuel’s life is at risk from Saul’s armies as he makes his way to Bethlehem to meet with Jesse. And, of course, in the Gospel reading, the man born blind is kicked out of the synagogue for refusing to change his story about Jesus giving him his sight.

Discerning the will of God is no guarantee that everything will work out in the short term. After David – Jesse’s eighth son, the one nobody would have expected to be chosen as king – is anointed, he spends years as a bandit in the wilderness with a group of similarly disaffected young men, before consolidating his power and being able to claim his throne. The writer of the books of Samuel says, “The Spirit of the Lord came mightily on David from that day forward,” but it takes a long time after that for God’s anointing to be fully in effect.

Both discerning God’s will, and then watching it play out, take as long as they take.

So how does discernment actually work? Most of us aren’t lucky enough to have God literally speaking in our ears, as Samuel does as he watches Eliab and Abinadab and Shammah and their brothers pass by one by one.

In the story of the man born blind, while God is of course actually present in the person of Jesus, we are shown a broad selection of ways to approach discernment, both helpful and not-so-helpful.

The first thing that anyone says in this story is when the disciples ask Jesus whose sin is to blame for the man’s state of blindness. Jesus responds “Neither this man nor his parents sinned; he was born blind so that God’s works might be revealed in him.” Right away we are on notice that people in this story are going to jump to conclusions and misinterpret God’s actions and desires.

There then follows a frankly comic series of exchanges in which the man who was formerly blind keeps telling everybody things that should be very very obvious, while all his interlocutors persist in misinterpreting what he says and refusing to believe what’s right in front of them.

When the man is brought before the Pharisees, they are divided: some conclude that since Jesus has healed someone on the sabbath, his deeds cannot be from God. Others conclude that if Jesus has the power to make someone born blind able to see, then that power must be of divine origin. When they ask the man himself, he says simply, “He is a prophet.”

When the man’s parents, in turn, are brought into the conversation, they are too terrified of the authorities to say much of anything at all. And so the Pharisees take it up again with the man himself, going round and round about sin and knowledge, whom God listens to and what God does, until finally the authorities, furious, accuse him of being “born entirely in sins” and drive him out.

What’s absent from this part of the story is any sense of reflection, of openness to new information, of any effort to actually listen to the will of God rather than simply knowing what it is already. The man who is no longer blind stands firm in his own truth; he knows what has happened to him and what it means to him. But everyone around him is flailing, acting out of fear, falling back on their comfortable certainties, terrified of having to admit that God is doing a new thing.

When the man who was blind is left alone with Jesus, there’s a palpable sense of relief. Now there’s some space. Now they can take a deep breath and be centered in the truth. Now the man can ask a simple question and get a simple, straightforward, truthful answer – Jesus is the Son of Man – and affirm, “Lord, I believe.”

Discernment requires space to think, to tell stories, to listen deeply, to reflect, to get back in touch with our core values. It requires the emotional safety to able to question our certainties and let go of old beliefs and interpretations that are holding us back, and to look for God moving in places that might be unexpected.

Next week, we’ll look at another story from John’s Gospel, the Raising of Lazarus, and how it connects to the concepts of “consolation” and “desolation” which are essential to discernment. But for now, it is enough to know what these stories show us: that the task of discernment is focused on finding God’s will; that it doesn’t guarantee that things will be easy or predictable; that it takes as long as it takes; that it requires time to reflect, and willingness to reconsider old certainties; and that it will work only if those involved tell the truth, as the man who was formerly blind consistently did even when it got him into trouble.

“Try to find out what is pleasing to the Lord,” writes Paul in Ephesians. It’s a great deal easier said than done. But we owe it to God and to ourselves to try.

Amen.

Leave a Reply