All Saints, Dorval

January 21, 2024

Who doesn’t know the story of Jonah and the whale? Along with Noah and the Ark, it’s one of the Bible stories we most like to illustrate and present to children – apparently there’s something about stories involving God, boats, storms, and animals. The idea of a human being swallowed by a whale and surviving the experience hits us in an instinctive place somewhere between humour and horror. (Unfortunately, the legend of James Bartley, a sailor who supposedly spent the night in the stomach of a sperm whale off New Bedford in the nineteenth century, is just that – a legend. Humans have occasionally found themselves in whales’ mouths, but actually being swallowed – nope.)

There’s so much more to Jonah than just the story of a zoological impossibility, though. The book of Jonah is just four chapters long, about 1300 words in English, in other words, about the length of my typical sermon. I highly commend it for your reading pleasure. It’s the only prophetic book that’s about the prophet’s experience, rather than his preaching (Jonah actually speaks only five Hebrew words of prophecy in the whole book), and it is simultaneously one of the funniest books in Scripture, and one of the most deadly serious.

The book begins without preamble: “Now the word of the Lord came to Jonah son of Amittai, saying, ‘Go at once to Nineveh, that great city, and cry out against it; for their wickedness has come up before me.’ But Jonah set out to flee to Tarshish from the presence of the Lord.” Then comes the part that most of us know, with God sending a great storm that swamps the ship Jonah has taken passage on, until the sailors throw him overboard (at his own request!) and he’s swallowed by the whale (or “big fish” – translations differ, and of course the writer of the book didn’t know the difference).

The second chapter of the book is the Psalm that Jonah prays from inside the fish’s belly, of which more later. Then the Lord speaks to the fish and it spews Jonah up on dry land (kids LOVE this part – he got puked! Hilarious!).

This is where today’s reading starts. God doesn’t even give Jonah time to dry off, let alone take a shower, before telling him again (one suspects with considerable annoyance) to get up and go to Nineveh. Jonah, apparently deciding that he’s not going to be able to get out of it so he might as well suck it up and get it over with, does so. He preaches against Nineveh and they turn from their evil ways. And that’s where today’s passage ends.

But there’s one more chapter. In it, Jonah yells at God, not for any of the things you might expect him to yell at God about, like having been picked in the stomach juices of a cetacean for three days, but rather because Jonah is mad that God was too merciful. “I knew you were a gracious God and merciful,” he rants; “slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and ready to relent from punishing. And now, O Lord, please take my life from me, for it is better for me to die than to live.” On that note, Jonah stomps out of Nineveh and sits down on a hillside, “waiting to see what would become of the city.”

We never find out what becomes of the city. The rest of the “plot” of Jonah is that God makes a plant grow up to shade Jonah from the sun, but then the next morning sends a worm to make it wither, and then Jonah yells at God some more. This is the final paragraph:

But God said to Jonah, ‘Is it right for you to be angry about the bush?’ And he said, ‘Yes, angry enough to die.’ Then the Lord said, ‘You are concerned about the bush, for which you did not labour and which you did not grow; it came into being in a night and perished in a night. And should I not be concerned about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who do not know their right hand from their left, and also many animals?’

That’s it. Jonah’s last words in the book are, “Yes, angry enough to die.” We never get an answer to God’s question, or a report of the fate of Nineveh. If you’re looking for tidy resolutions and straightforward answers about God’s will, look somewhere else. (Maybe the book of Proverbs.)

But by that very token, the book of Jonah is endlessly fascinating for such a short, blunt text, and richly abundant in meaning, if not in answers.

So what are some of those meanings? (Just a selection, because entire books have been written on this subject!)

First of all, Jonah shows that you can do God’s will while being cranky and contrary. Jonah spends literally the whole book in a rage of one kind or another (well, except the part where he’s napping on board ship). He doesn’t want to do what God asks him, and when God denies him the pleasure of watching the people of Nineveh get smited to death, he sits down and sulks. Nevertheless, he does in fact deliver the prophetic message he’s called to preach (eventually …) and as a result the city of Nineveh repents in sackcloth and ashes.

Jonah, the only person in the story who starts out believing in the God of Israel, is by far the most resistant to God’s voice and will. Everyone else is radically – not to say improbably – open to God’s message. The people of Nineveh hear the world’s shortest prophecy and instantly believe – and change their whole lives. Aboard the ship, Jonah tells the sailors that he worships “the Lord, the God of heaven, who made the sea and the dry land.” They are terrified, knowing he is fleeing from the wrath of his God, and they beg that same God for forgiveness while throwing Jonah overboard, and even afterwards, “feared the Lord even more, and they offered a sacrifice to the Lord and made vows.” It’s like we’re on Oprah – YOU get converted! And YOU get converted! EVERYBODY gets converted! Except Jonah, who’s still cranky.

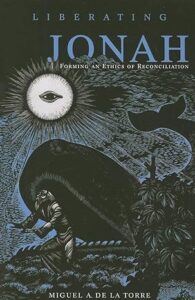

And part of why Jonah is cranky is absolutely valid. An aspect of the book that has been brought to the fore in recent years is the way that it dramatizes the complicated relationship between an oppressor and those who are oppressed. Jonah lived – if he actually existed as more than a character in a parable – in the eighth century before Christ, at a time when Assyria, with Nineveh as its capital, was a great power in the region of the Near East. As Miguel de la Torre puts it in his book Liberating Jonah: Forming an Ethics of Reconciliation, “Assyria was … an evil empire, the mortal enemy of Israel, whose fundamental purpose was to destroy Jonah’s people, the Israelite nation, and its way of life. For the marginalized Israelites, Nineveh came to symbolize violence and cruelty.”

From this perspective, Jonah’s digging in his heels at God’s initial prophetic call, and his furious outburst when the Ninevites do in fact repent, are more understandable. Jonah doesn’t want Nineveh to be spared punishment! He wants them to get what’s coming to them for the way they’ve treated him and his people!

This is what I was referring to when I said that the book of Jonah was deadly serious. It also, incidentally, proves wrong any claims that the Old Testament God is exclusively wrathful and vengeful; God, in this story, is far more merciful than Jonah! Jonah is, in fact, being asked to follow precisely the most difficult command of Jesus: to love his enemies. In his excellent book, De La Torre does not offer any easy answers, and neither does the book of Jonah itself, but it certainly provokes thought about the nature of forgiveness, reconciliation, and divine love.

The final element I want to highlight in Jonah is the typology, which is a fancy word for “something in Scripture that symbolizes something else.” As I was rereading the four chapters while preparing this sermon, I underlined the description of Jonah asleep in the hold of the ship and made a sarcastic note in the margin that this was the only way in which Jonah resembles Jesus (who famously napped in an open boat during a storm on the sea of Galilee).

Of course, it’s not actually the only way Jonah resembles Jesus: Jonah, like Jesus, spent three days in a very confined space on the border between life and death. One of the mildly inexplicable choices made by the BAS is the failure to include Jonah’s prayer from the belly of the fish in the liturgy of the Great Vigil of Easter; the parallels with Jesus in the tomb are so very striking and instructive.

I could go on – there’s so much in this book! – but this sermon is already considerably longer than the book of Jonah itself. You should all read it, and let it provoke your mind and stir up your spirit to thoughts of cranky prophets, repentant oppressors, and how to pray even in an impossible situation.

Amen.

Great food for thought! Thank you, Rev. Grace!