All Saints, Dorval

March 3, 2024

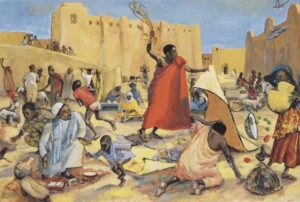

“Jesus Drives out the Merchants,” Jesus Mafa, Cameroon

I confess: I sometimes get really tired of refuting antisemitic and anti-Jewish interpretations of Scripture. Especially since I don’t actually think that anyone in this congregation necessarily thinks that the Jewish faith or the Jewish people is inferior in the first place.

I would much rather talk about Paul’s idea that “the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom”, or about the Ten Commandments, than tackle the history of misinterpretation of Jesus’ disruption of the Temple Court (and, in fact, when I preached on these readings three years ago, I just ignored the gospel passage; the whole sermon was about the Fourth Commandment, on the topic of sabbath).

And yet, if we look away from unpleasant ideas for long enough, eventually they’ll pop back up to bite us.

As I was reading commentaries this week in preparation for this sermon, I came across some doozies of anti-Jewish readings of this story. For example, apparently at some point in history this passage was interpreted together with the story of the wedding at Cana, which comes right before it in the second chapter of John. The water for purification in the Cana story was taken to symbolize Jewish law and ritual, which Jesus replaced with the wine of the Eucharist. And thus the story of the “cleansing” of the Temple, following immediately after, was also read as a call for Christianity to replace Judaism – the old, poisonous gospel of “supersessionism”.

To be clear, the commentary I was reading did not espouse these views; it quoted them in order to refute them. But it can be mind-boggling to realize what people honestly believed in prior generations.

And even today, the hymn we sang just before the gospel reading perpetuates some milder, but still inaccurate and unhelpful, stereotypes: describing the Temple as “a shameful robbers’ den”, and implying that there was something wrong about the practices of changing money, selling animals for sacrifice, and designating a particular space for the gentiles to be in the temple.

In fact, all these practices have simple explanations: it was considered sacrilege to pay the Temple dues with money that had the Roman emperor’s head on it, so those coins needed to be exchanged for the ones that were used inside the sacred precinct. Animals brought from far away might get hurt, be stolen, wander away, or die on the journey, so it was much safer to purchase them onsite. And as for excluding people – religions are actually allowed to have standards about who enters their holy spaces. Having areas of the Jewish temple that only Jews are allowed to enter is not being exclusionary.

So, if Jesus isn’t declaring Judaism or Temple worship to be corrupt and in need of replacement, what is he doing in this story?

First of all, it’s important to realize that John’s narrative of Jesus’ words and actions is firmly grounded in the Jewish prophetic tradition. His disciples recall a verse from the Psalms in interpreting his behaviour, and he draws on a long tradition among the Jewish prophets of criticizing worship practices that did not result in moral and ethical behaviour the other six days of the week.

Dr. Amy-Jill Levine, a well-known scholar of the New Testament who is also Jewish, has written extensively on this passage. In her book Entering the Passion of Jesus, she says that by this action, Jesus “is alluding to Zechariah 14:21, the last verse from this prophet, ‘and every cooking pot in Jerusalem and Judah shall be sacred to the Lord of hosts, so that all who sacrifice may come and use them to boil the flesh of the sacrifice. And there shall no longer be traders in the house of the Lord of hosts on that day.’ In John’s version of the Temple incident, Jesus anticipates the time when there will no longer be a need for vendors, for every house not only in Jerusalem but in all of Judea shall be like the Temple itself. The sacred nature of the Temple will spread through all the people. He sounds somewhat like the Pharisees here, since the Pharisees were interested in extending the holiness of the Temple to every household.”

And there shall no longer be traders in the house of the Lord of hosts on that day. Far from rejecting the Jewishness of the Temple, Jesus is building on specific prophecies about it that he hopes to see fulfilled.

Levine’s book is called Entering the Passion of Jesus, because Mark’s, Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts of this episode all put it just before the Crucifixion. But in John, it’s several years earlier – at the very beginning of Jesus’ ministry. Which in some ways rings true – it can very easily be seen as the action of a young, untested prophet who wants to make a splash and hasn’t really learned yet where to draw the line between being provocative and ticking people off.

Interestingly, though, in John’s account, the response to this action actually seems to be pretty low-key. Nobody scolds Jesus or threatens to have him arrested. In fact, they seem to take it pretty much in stride. (As Levine also points out, the Temple precincts covered twelve acres, so it’s highly unlikely that most of the people who were there that day even noticed Jesus’ little demonstration.) As John puts it, “The Jews then said to him, ‘What sign can you show us for doing this?’” Not “how dare you!” or “you must have a demon!” Just – clearly something prophetic is going on here, can you help us contextualize it within that tradition?

Jesus, as usual, refuses to give easy answers. “Destroy this temple,” he says, “and I will raise it up again in three days.” His interlocutors are understandably confused, and John helpfully explains that Jesus means his body.

But of course, by the time John was writing, this Temple had in fact been destroyed, by the Romans, and all Jews – both those who understood Jesus to be the Messiah and those who didn’t – had to reckon with that trauma and rupture in their understanding of their history and of themselves. They were all looking for answers as to what these terrible events meant. Sadly, the answers that the Jewish and the nascent Christian communities found too often led them apart from each other, rather than towards each other, over the subsequent centuries.

There are lots of fruitful ways to look at this text that don’t involve misrepresenting and denigrating our Jewish cousins by comparison. Just a few, each of which could be its own sermon, that arose in my weekly colleague discussion group:

What does this passage say to those of us who are deeply concerned about injustice in the world, but don’t feel like we get any results – or even get anyone to pay attention – until we lose our cool in public?

What does it mean for Jesus to be doing something unusual, extreme, dramatic, in a place that’s usually very regimented (like – for example – a typical Anglican Sunday liturgy)?

What comes to mind when we think about how much easier it is to destroy something – knock over a table, send some coins flying, tear down a whole temple in a few days that took forty-six years to build – than to build it? And how do those thoughts change when we reflect on how destruction is never the end, whether what emerges from that destruction is a reformed faith, a risen Saviour, or the two-thousand-year Jewish rabbinic tradition?

As with any Bible passage, this story is rich with a multiplicity of meanings. Any of them can be true – as long as they encourage us to love our neighbour, to seek God, and to be transformed in the direction of greater compassion and generosity.

May we, like the Pharisees of Jesus’ time, seek to extend the holiness of our sacred spaces into every household in our community and every moment of our lives.

Amen.

Leave a Reply