A sermon guest preached by Gretchen Wolff Pritchard, April 7, 2024 (Easter II, Year B)

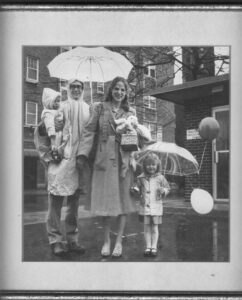

The Pritchard family coming out of church on Easter Sunday, 1983.

Today’s story is commonly known as “Doubting Thomas.” And oh how easily we identify with Thomas. He missed the party. He didn’t see the angel at the empty tomb. He wasn’t there when Jesus appeared among his friends and blessed them. He doesn’t feel it, he doesn’t get it, because he hasn’t seen it for himself. “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.”

Wait a minute, though. If we were Thomas, is that what we would say? “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands …”? The other disciples have been insisting that Jesus is alive: he was in the room with them; he spoke with them; he assured them of God’s peace and blessing; you would think Thomas would be saying, “Unless I hear his voice … unless I see him, warm and breathing and walking around … unless I can touch his living flesh …” but … his wounds?

Maybe this story isn’t mainly about doubt, or about “seeing is believing;” maybe it there’s something else about it that’s kind of hiding in plain sight.

As some of you know, I spent thirty years doing children’s ministry, and writing and illustrating Bible stories and other church materials for children. In those years I learned a great deal about children’s spirituality—much of it from my own three children, of whom the oldest is your rector. And she has given me permission to tell some stories this morning that feature herself as a small child.

I started producing a weekly illustrated children’s bulletin called “The Sunday Paper” that I sold to churches, when Grace was a toddler. Most of the time, I was home with Grace; I worked on The Sunday Paper during the blessedly long and predictable afternoon naps that this model child used to take. My desk was always covered with paper and pencils and India ink; luckily she wasn’t interested in the ink, but we did a lot of drawing together, and because I trimmed the large sheets of art paper to 8½ by 14 inches to make the Sunday Paper pages, I had a constant supply of trimmings. She liked me to cut the trimmings into little bookmark-sized pieces for her and make drawings on them; she would then carry the little drawings around and use them as toys. We got into a routine where every night at bedtime I would draw a “sleeping baby” for her on one of the trimmings, and she would take it to bed with her (eventually her crib would have eight or ten of these little sleeping babies in it)—a simple drawing of a little girl lying in her sleep sack with a pacifier in her mouth and the bars of the crib behind her.

Of course we also read books together, and sometimes she wanted to see the work I was doing, so I would show her the drawings I was making of Jesus and his friends, and tell her those stories too. The children’s bulletins I was making were based on the Sunday Bible readings for church, so in due time the story I was illustrating was the story of Lazarus, and of Mary and Martha crying, and Jesus crying with them.

And that night—and for the next several nights—instead of a sleeping baby, she asked for a “crying Jesus” to take to bed with her.

The story of Lazarus from the Gospel of John—the same Gospel from which our story about Doubting Thomas is taken—is John’s preview of the way of the Cross: on behalf of his friend Lazarus, Jesus confronts death face to face as a rehearsal of his cosmic confrontation with death on the Cross. And it is not easy. Jesus sighs and groans; Jesus weeps. Grace’s intense reaction to my drawing of Jesus crying—her repeated request that I draw it again, for her to take to bed—showed me what I knew already from my own heart: it is terribly important to us to know that Jesus wept. He cries with us; he cries for the anguish of the whole world. We are told that God will dry every tear … good news that is much more believable because we know that God himself has wept those tears with us.

Now listen to this story from a book on children’s spiritual development that came out around that same time, written by a mother with young children.

Once, on a visit to an art museum with my three-year-old, I tried to hurry her past a room filled with paintings of the crucifixion. But a portrait of Christ wearing a crown of thorns caught her eye, and she refused to budge. “Why is Jesus bleeding?” she asked. Her Sunday school curriculum had, quite appropriately, always shown him smiling.

“Those branches he’s wearing on his head have prickers on them,” I said quickly, stooping to pick her up and carry her out of the room.

But she squirmed out of my arms. “Why is he wearing branches?”

“Well, some people were making fun of him because he said he was a king, and they wanted to put a pretend crown on him,” I replied. “Now why don’t we go into the next room where they have lots of nice pictures of babies and flowers?” I kissed her cheek.

“Is he sad?” she persisted.

“Yes, the person who painted the picture is showing us that Jesus felt very sad.”

“Did he die?”

“Yes,” I said, “he died on the cross.”

“Well, anyway,” she reflected, her voice trembling, “in the spring, his daddy will make him alive again!”

This little girl has encountered a deeply disturbing image, and is asking her Mommy for help in dealing with it. But instead of facing it with the child, the mother’s response is to protect her, by trying to push the image away, change the subject, think about something nicer. But the little girl is not cooperating; she is persistent and determined, coming back again and again with questions that probe the heart of this image. Finally, she gives up on Mommy, and instead turns to her own resources—her treasurehouse of stored images, gleaned from books and stories, fairy tales, holiday celebrations, and her own experience of the natural order—and finds the building blocks of hope. “In the spring, his daddy will make him alive again!”

Jesus does not always smile. Sometimes he weeps. Sometimes he lashes out in fierce anger and indignation. Sometimes he is asleep and oblivious while those around him are screaming for help. Sometimes he groans and sweats blood. Sometimes he cries out with a loud voice, “My God—my God—why have you abandoned me?”

Another story about Grace; this time she’s, I think, three. She had a favorite book, William Steig’s Sylvester and the Magic Pebble. Sylvester, a young donkey, finds a magic pebble that can grant wishes. On his way home to show it to his parents, he meets a hungry lion, and, in his panic, says, “I wish I were a rock!” The magic pebble turns him into a rock. When he doesn’t come home, his grief-stricken parents search everywhere for him, but of course they can’t find him. The book is poignant, sad, and suspenseful, and eventually it has a happy ending—through a series of lovely coincidences, Sylvester, in the springtime, becomes himself again. We read it over and over again; I still know parts of it by heart.

We had a crucifix over our bed. One morning as she was “helping” me make the bed, Grace looked up at the crucifix.

“That’s Jesus,” she said. “He can’t get down.”

“Well,” I answered, “he could have gotten down; but he loved us and he wanted to save us, so even though it hurt, he stayed there.”

“He died.”

“Yes, he did. And they put him in a tomb. And do you remember what happened next?”

She thought for a minute.

“He rose from the dead! He became himself again! Just like Sylvester!”

***

If I learned one thing in all those years of teaching children in the church, it is this: children do not want to be shielded from the Cross. Children know that the world is not all flowers and babies. It is not the Gospel of the Cross that terrifies children. What terrifies children are the false Gospels: the false Gospel of sentimentality that tries to pretend the world is wall-to-wall flowers and babies, and the false Gospel of moral lessons, of high standards and good behavior, that binds heavy burdens on children and leaves them exposed in all their bumbling weakness and hopelessness before the righteous judgment of their parents and of God.

And those false Gospels should terrify us, too; because they are false. They let us down; they do not stand the test of real life. The world God has made, and into which Jesus came—the world for love of which he wept and suffered and died—is, at its heart, a mystery, and the ways of God are a mystery. Jesus saved us, not by magically wishing away all the hurt, not by showing us how to be so good that nothing bad will ever happen to us—but by entering with us into the pain of an unsafe, unfair, unpredictable world, going down, down, down into its pain, letting it do its worst … and coming out on the other side, with life out of death.

The risen Christ who meets his disciples is insistently intimate, physical, and fleshly. This is crucial and important: the risen Christ is not a demigod or superhero or mythical figure who is merely spiritual or symbolic or idealized. Far more theologically significant than Thomas’s doubting is Thomas’s deep awareness that the living Christ is wounded—his new life does not magically undo or erase the agony of our earthly and physical life or the pain inflicted on us by our own sins and the sins of others, but, rather, transforms it in some way we cannot yet understand.

Jesus told us to become like children; we have a lot to learn from the children. Children are used to things being hard to understand, and hard to control. Children are used to the hard work of struggling for meaning, claiming hope, and thinking in stories and images. “In the spring, his daddy will make him alive again!” “Just like Sylvester!” Children still do what communities have done throughout history with their stories, but what we so often fail to do: they engage the story with their whole selves, until they have made it their own—until the story has changed them. And Jesus told us to be like children: to open ourselves to the story and let it change us.

Children are drawn to stories of struggle and loss, of courage and sacrifice, of terror and unfairness, because they themselves, more than we want to admit, must deal with these things. Folktales and fairy stories, with their witches and monsters, evil stepmothers and mean stepsisters, dark forests and hungry wolves—stories like Sylvester and the Magic Pebble and some of the modern myths like Star Wars and The Lion King and Harry Potter and the Narnia books and The Lord of the Rings—tell the truth in language that children can understand. And these stories go on, also in language that children can understand, to offer hope: hope that the helpless will find help in unexpected places; hope that a small deed of kindness may make the world new; hope that the despised and deformed will prove to be beautiful and of royal blood; hope that out of suffering and loss will come reconciliation and new life.

When the people of Israel had lost everything, and were in exile in Babylon—their temple destroyed, all their holy things desecrated, their homeland in ruins—Ezekiel had a vision of a valley full of bones, dead, picked clean, bleached and dried out. The spirit of the Lord asks him, “Can these bones live?”

We read this story at the Easter Vigil, and ask, Can God bring life out of death?

Ezekiel hedges his bets: “Lord, you know the answer to that one, not me.” And the Lord raises the bones to new life—but not by direct power or a direct order. No, the Lord commands Ezekiel to “prophesy” to the bones: to tell them, “Hear the word of the Lord,” and Ezekiel obeys: “So I prophesied as I had been commanded; and as I prophesied, suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone. … I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude.”

It is the work we bring to the story that, literally, brings it to life. It is the work that Ezekiel brought to the dry bones at God’s command; it was the work the child in the art gallery brought to the disturbing image of Jesus wearing the crown of thorns—the work that Grace brought to the image of the crying Jesus and the crucified Jesus—this work of hearing the story and letting it change us—that enables the story to live, and to give its life to us.

Grace’s little sister, Margaret, latched on to the story of the Dry Bones in the same way as Grace had grabbed hold of the image of the crying Jesus. We were doing an Easter pageant at church in which the kids acted out the Dry Bones story as it was read aloud: lying down on the floor, then, as someone rattled castanets, getting up, jerkily, stiffly, then standing tall, then taking hands and dancing in a ring. Margaret was too little to participate but she had watched the rehearsals as well as the pageant itself, and some days later I heard her chirping to herself, “And the dry bones said, ‘Son of man, can we live?’ And the Son of Man said, ‘Of course you can!’”

Easter does not come after the Cross, it comes out of the Cross. The Cross is not an embarrassing blot on a spring postcard full of babies and flowers—something we can edit out so as not to upset the children; something we can skip, and jump straight to the happy ending. The whole story is of both the Cross and Easter.

And in Thomas’s insistence on testing the reality of Christ’s woundedness we learn how very strange and mysterious is this whole business of resurrection. It does not fit into any of our easy categories. Not only does it rule out the Marvel Comics superhero savior who exists only in our imaginations; it also does not give back to the disciples their dear familiar friend, just as he was before, as if the cross had all been a narrow escape or a bad dream. Nor does it (as the disciples may well have expected) signal the beginning of the End Times when God would bring about the fulfillment of all things. Nor (as many, many Christians wishfully claim) is it evidence for “life after death” or the immortality of the soul, or a promise that we, in turn, will go to heaven when we die.

It is the work we bring to the story that, literally, brings it to life. And if the story is to live for us, we need to bring ourselves to it, to enter it, to speak over it as God commands us, as God commanded Ezekiel, to challenge and test it, as Thomas challenged it. It is not enough to passively say, “I dunno, Lord, you tell me.”

And Thomas tested and challenged the story in community: the other disciples did not write him off when he doubted, and he did not quit their fellowship even though he must have thought they were all lost in a fantasy world of wishful thinking. The story lives when we step into it, when we appropriate it as children appropriate their stories, when we give ourselves together to its power, like children acting out a story in their play.

We need to tell, and hear, the stories, again and again, as children do with the stories that most stir and trouble them, that raise and answer questions, that stretch and pull at their imaginations and make them work, assembling from these building blocks of stories, images and experiences, a framework for meaning and hope. We need to come back, again and again, to this table, be nourished—literally—by the heart of our story: its promise of life out of death; to receive the story concentrated into a morsel of bread, a sip of wine, that we absorb into our very bodies, make part of ourselves. We need to replenish, continually, our treasurehouse of stored images and experiences, so that we will have the resources to claim this hope, this promise.

Jesus wept. Jesus groaned and sweated blood. Jesus bled and died. And in the springtime, his daddy made him alive again—still wounded, but transformed, the First-Begotten of the Dead. This wounded Saviour, this Lamb who was Slain, promises us life, life in abundance—not life after death, not life instead of death (not a safe tame world of babies and flowers), but life out of death.

And when we come, with open hearts, to the story—with all our questions, with all our tears and sorrow and doubts and wounds—his daddy will make us alive again too.

Amen.

Leave a Reply