All Saints’, Dorval

November 24, 2024

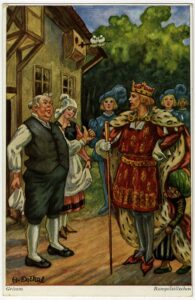

Illustration for “Rumpelstiltskin,” H. Dočkal, c. 1928. Wikimedia Commons.

As of this weekend, I have kept my Duolingo streak going for exactly four years and nine months. I’m not sure it’s actually improved my French that much, but I’m certainly way too stubborn to drop it anytime soon!

This week, I have been presented with a unit on fairy tales, and I’m learning fun new vocabulary like “La princesse cachait ses épees sous son lit,” “Elle marchait dans la forêt lorsque le loup l’a vue” and “La sorcière lui a jeté un sort ». Needless to say, there are a lot of royalty in these exercises: not just the sword-hiding princess, but le prince qui était transformé en grenouille, la reine très puissante, and le roi que tout le monde adore.

Fairy tales are full of princes and princesses for obvious reasons: in the times before photography and mass media, royalty were remote, mysterious figures with almost mystical powers, dressed in unimaginably elaborate clothing and living lives an ordinary person could barely imagine. But the kings in fairy tales rarely if ever occupy themselves with the actual business of governing a kingdom. They don’t levy taxes or meet with their counselors about infrastructure projects or worry about usurpers; they seem to spend most of their time marrying off their daughters, offering to give away half their kingdom, or both at once.

Today is the feast of the Reign of Christ, a relatively new observance in the church calendar; it will only reach its centenary in 2026. It is still a controversial celebration, having been instituted by a Pope who was at least as alarmed by socialism and anti-clericalism as he was concerned about the rise of authoritarianism in Europe between the wars. Many good liberal democrats of today find it a bit embarrassing to celebrate Jesus as King, and certainly it’s felt even a little bit more awkward since we’ve had an actual king whom we all know to be an extremely complicated and imperfect human being.

And yet. I can’t help taking an almost childlike pleasure in this occasion – and I think “childlike” is precisely the way we should approach the Reign of Christ, while also retaining a very adult consciousness of exactly what we are doing and why. So why, despite everything, do I love this feast?

First of all, it wraps up the liturgical year in a satisfying manner. Instead of just another few random slices of scripture, we get a coherent celebration that connects to the themes of saints, judgment, and God as creator that have prevailed during the latter part of the long season after Pentecost, and points forward to Advent by anticipating the theme of God coming again in glory.

More importantly, though, the scriptures for this feast reveal a king who is much more like the king in a fairy tale than the ones who have actually ruled on earth throughout human history. Jesus’ reign does not support or even replace our human rulers and politics – thanks be to God for that! – rather, it annihilates the whole concept of human government. When – as the Episcopal catechism puts it – Christ comes “not in weakness, but in power” and makes all things new, there will be no more need for our chaotic and doomed attempts to rule ourselves, because the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.

And Jesus does, in fact, behave much more like the king in a fairy tale than one who’s concerned with the practical logistics of governance. He talks in riddles – just look at how he evades Pilate’s questions in the gospel reading from John. He seems positively eager to give away half his kingdom to anyone who follows him, who loves God and loves their neighbour. And the whole story is building toward the day when the prince and princess will get married and everyone will live happily ever after.

Like the image of the king, God knows that the image of the “royal wedding” or “fairy-tale wedding” is not one that has served us well when we’ve tried to translate it into mundane reality. From the Charles and Diana disaster to the unfortunate tendency of ordinary women who have been raised on the princess ideal to find themselves trapped in toxic relationships after the wedding, we have rightly learned to be suspicious of what hides behind the shiny, tulle-covered façade.

And yet once again, Scripture offers the reality to which our daily existence can’t live up, and shouldn’t try – but which is nevertheless valuable if we can keep it in its proper perspective.

The Revelation to John, the book from which our second reading is taken, is a book boiling over with rage against the empires of the world and how they abuse and oppress the helpless and marginalized – which presents its entire action in terms of kings and a royal wedding. In today’s reading, from the first chapter, Jesus is “the faithful witness, the firstborn of the dead, and the ruler of the kings of the earth.” And he makes “us a kingdom, priests serving his God and father.” This king makes all his people royal priests along with him – an action which of course is logically impossible, but that never stopped Jesus or any other fairy-tale king before.

The book goes on to describe, in frankly gruesome but fascinating detail (just the kind that kids like best) all the ways that Babylon (which in this narrative stands in for Rome) is overthrown and punished for its wickedness. And then it concludes with the staggering vision of God’s new creation, a city literally made of jewels, fifteen hundred miles long and wide.

The marriage metaphors come thick and fast: the city is “coming down from heaven, prepared like a bride adorned for her husband;” “the marriage of the Lamb has come, and his bride has made herself ready;” “the Spirit and the Bride say, ‘Come,’ and let those who are thirsty come; let those who desire take the water of life without price.”

For all their unfortunate references in our contemporary culture, for all their heteronormativity and gender binaries and potential for anti-feminism, these images have an extraordinary hold over our imaginations – and, I would argue, rightly so. (They’re also, once you so much as scratch the surface, incredibly queer, but that’s another sermon.)

We should think of the image of Christ and His Bride in Scripture not in Disney princess terms, but in Shakespearean comedy terms – the marriages that conclude the plot represent the healing of division in the community, the reaffirmation of life, love and hope, and the prospect of peace and happiness for all, not just the bridal couple.

There’s a reason that the fairy tales end with “and they all lived happily ever after,” because that is, as human beings, our deepest desire and profoundest hope: to be assured that somehow, someday, we will get beyond the storms and sorrows of this life and come safely to harbor, that we will be able to live in peace, each one under their own vine and fig tree, with no one to make us afraid.

Jesus, the fairy-tale king, promises us that the happily ever after is real. It will happen far beyond our own mortal deaths, in a realm unimaginably distant from our present experience – and yet familiar, because it is where God is; familiar as a well-loved fairy tale. Jesus is, in the words of my Duolingo lessons, le roi que tout le monde adore, and for once, that adoration is not misplaced.

Our fairytale king will solve the riddle, marry the princess, and recklessly give away his kingdom to those who follow him. And we’ll all live happily ever after.

Amen.

Leave a Reply