All Saints’, Dorval

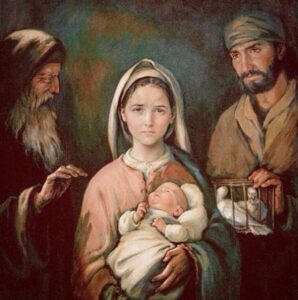

Feast of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple (Candlemas)

February 2, 2025

[sing]

This child must be born so the kingdom may come;

salvation for many, destruction for some:

both end and beginning, both message and sign,

both victor and victim, both yours and divine.

We sang this hymn from the new Sing a New Creation hymnal back in December, when my parents were visiting, so it was the first time they had heard it. After the service, my mother remarked that she liked it, but was a little taken aback by the second line of that verse: “salvation for many, destruction for some”.

I shrugged, and reminded her – “it’s scriptural”! And we started talking about something else.

Today’s gospel reading is the scripture that that line is referring to.

Then Simeon blessed them and said to his mother Mary, “This child is destined for the falling and the rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed – and a sword will pierce your own soul, too.”

It’s a hard passage to parse. What does it mean that “a sign will be opposed”? Who are those who will fall and rise, and what inner thoughts will be revealed? And how is it all connected to the sword that will pierce Mary’s soul?

It takes reading the rest of the gospel to even begin to have answers to these questions, and in many ways, Simeon’s prophecy is still being fulfilled.

Certainly, Jesus and his cousin, John the Baptist, whose miraculous birth has also been attended with prophecies and psalms in the first chapter of Luke, have an outsize impact on the events and power structures in their time and place, even though they both end up being executed by the authorities. From Herod and Pilate to soldiers and tax collectors to fishermen and prostitutes, Jesus’ presence and preaching does lead to the falling and rising of many.

And “a sign that will be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed” – even if we can’t quite figure out the grammar of the sentence, the connotation is clear: Jesus is a sign that comes with, if not actual violence, at least a sense of crisis, of drawn battle lines: the clarity of knowing where you stand even if that stance comes with uncomfortable consequences, the relief of no longer being asked to fake it. The coming of Christ reveals who people really are.

Simeon’s prophecy to Mary specifically, that a sword will pierce her soul, is the easiest part to parse: this is, after all, a woman who a scant three decades later will be watching her son die slowly and painfully in front of the crowd that had howled for his blood. But I think it’s important to remember that this is about much more than Mary’s personal experience; that Mary is also the singer of the Magnificat, that great hymn of reversal that tells of the hungry fed and rich sent empty away; Mary is in many ways the person who understands Jesus’ mission more fully than anyone else other than Jesus himself, and the piercing of the sword did not begin with the Crucifixion (or, indeed, end with the Resurrection). Bringing up a child is hard. Bringing up a child that you know is destined to change the world, is unimaginably harder.

But Simeon’s prophecy isn’t just for the people in that time and place. All of it is still true. The falling and rising of many – salvation for many, destruction for some – the sword that will be opposed, the thoughts that will be revealed, and the sword that will pierce the soul.

I was born in 1978. I came of age in a time in world history when, for a brief, heady moment, it really seemed like humanity had figured some things out. The world freed itself from British imperial rule. Civil rights, the rule of law, and social welfare had taken hold in many societies. The Berlin Wall fell, and then the Soviet Union. South Africa had free and fair elections. Liberal democracy seemed poised to usher in a new age of peace and equality across much of the world. We had saved the bald eagle, cleaned up our rivers and were well on the way to closing the hole in the ozone layer.

And then came September 11, 2001, and the invasion of Iraq, and global climate change, and over the past quarter-century we have watched as that optimistic consensus slowly, and then rapidly, fell apart. Fascism is resurgent around the globe, wars that had seemed unthinkable are raging, (don’t even get me started about the tariffs), and suddenly our times don’t seem so special and hopeful anymore.

Signs are being opposed, people are falling and rising, the inner thoughts of many are being revealed (remember when you didn’t know everything your neighbours were thinking because the internet didn’t exist yet?), and we are realizing that we are unlikely to get out of here without a sword piercing our own souls. Those of us who had gone through life on the unspoken assumption that history was something that happened to other people, are now receiving a rude awakening. We have trusted in the institutions of a liberal democratic consensus to protect us, and increasingly it looks like those institutions are shaking on their foundations.

It is very possible that, in the coming years, as nations convulse and the rights and safety of people are threatened, that Christians are going to have to remember how not to follow the rules. We are going to have to put our skin in the game. There are going to be people who need protecting in ways that the authorities may not approve of.

I’m not saying it’s happening here in Canada today – though it most definitely is happening only a hundred or so kilometres to the south of us, and I don’t know how long we’re going to be able to feel that we’re exempt. But we need to be prepared for the choice. The mighty are going to be cast down, and the sword will pierce the soul of Christ’s mother, and we may not have the option of staying on the sidelines. Salvation for many, destruction for some, and you can’t just stand by and not choose. As Dorothy L. Sayers (who else?) put it, “in us or upon us, the prophecies must be fulfilled.”

This is nothing new. It only feels new because the last few decades have been such an anomaly of peace and prosperity. From the very first Christians risking death by the lions in the Roman arena, to the Reformers sticking out their necks to bring the Bible to people in their own language, to the Civil Rights movement that is within the living memory of many in this room, civil disobedience on behalf of the marginalized is a proud Christian tradition.

I tend to forget that not everybody knows the story I’m about to tell, because I don’t like to act as though it somehow redounds to my credit when it happened 35 years before I was born. My grandmother, Marion van Binsbergen, was the daughter of a Dutch judge and a mother who has been accurately described as “an Englishwoman with authority issues“. As the Second World War dragged to its bitter end, she was confronted one night in the living room of the big house outside Amsterdam where she was living, by a local Nazi collaborator who had doubled back after a police raid to try to find the Jewish family they suspected she was hiding under the floorboards. The family, the Polaks, had in fact just emerged from their cubbyhole, because the baby was crying and they hadn’t had time to drug her. Acting in a split second, my grandmother grabbed the revolver that had been given to her by a fellow resistance member, and shot the Dutch Nazi dead. She smuggled the body out of the house with the help of a sympathetic undertaker, and nobody ever asked what had happened to him. (If she knew his name, I’m not aware of her ever having told us.)

I’ve been hearing this story since before I can remember. And so perhaps I’m at least a little less surprised than I might be – though no less horrified that it has come to this – by the resurgence of a murderous ideology, and the prospect of having to resist it in ways that go well outside the kind of behaviour expected from good Anglican daughters of government employees.

If it comes to that, I’ll be scared stiff. So will you. So was my grandmother, for the whole duration of the war, but she survived the occupation, the starvation, and seven months in a Nazi prison and died in bed at ninety-six in 2016.

We don’t know what will come. We don’t know what God will ask of us.

The hymn with which I began? Here’s how it ends:

But Mary, consenting

to what none could guess,

replied with conviction,

“Tell God I said ‘yes’.”

Mary consented to serving God by bearing his Son. Neither she nor anyone else could have had any idea how that would play out. A sword pierced her soul; what was most precious to her died before her eyes in blood and agony. But on the far side was victory and new life, and the deep assurance that she had been faithful to the will of God.

Amen.

Leave a Reply