All Saints’, Dorval

Epiphany VI, Year C

February 16, 2025

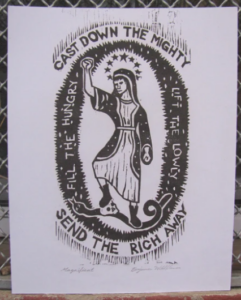

Ben Wildflower, “Magnificat”

Here’s a dirty secret about preaching:

Very frequently, a preacher will spend all week carefully, thoughtfully preparing a sermon on the assigned readings, and then, while reading the Gospel or preaching the actual sermon on Sunday, will have a flash of insight about something completely different in the text that they hadn’t even noticed.

(At least, this happens to me all the time. Perhaps my colleagues’ brains are more organized.)

Two weeks ago, when I gave my sermon on the Feast of the Presentation, I referenced the Magnificat, the Song of Mary, the line that says that God “will fill the hungry with good things, and the rich he will send empty away.”

This is generally interpreted as a threat against the rich, proof that God is on the side of the needy – which it absolutely is.

But it occurred to me that perhaps that’s not all that this line implies; perhaps it also could be understood to mean that when the rich are sent empty away, that’s the beginning of the process of them coming to know God, because once their riches are no longer getting in the way, they can begin to experience God’s power and providence in the way that the poor already do.

And so when I read this week’s gospel, I thought of this insight again. The Beatitudes that are most familiar to us – blessed are the poor in spirit; blessed are the pure in heart; blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness – come from the gospel of Matthew. Luke’s are more practical and hard-hitting. Blessed are the poor. Blessed are the hungry. Blessed are those who weep. And unlike Matthew, Luke also includes woes for those who are rich, full, and laughing. Luke is less interested in the state of people’s souls than in the state of their stomachs.

The rich God has sent empty away. Woe to you who are full now, for you will be hungry.

These sound threatening, but they’re actually simple statements of fact. It’s really hard to believe in, trust, and follow God if you’ve got too much wealth. Wealth gives you security and self-satisfaction, which, make you much more likely to think of yourself as the centre of the universe, and that in turn leads you to behave in ways that are very bad for your soul, long-term.

As the reading from Jeremiah said: “Cursed are those who trust in mere mortals and make mere flesh their strength, whose hearts turn away from the Lord. They shall be like a shrub in the desert, and shall not see when relief comes.” On the other hand, “Blessed are those who trust in the Lord … They shall be like a tree planted by water, sending out its roots by the stream. It shall not fear when heat comes, and its leaves shall stay green; in the year of drought it is not anxious, and it does not cease to bear fruit.”

Feeling like you’re the centre of the universe because you can flash your credit card and solve pretty much any practical problem, unfortunately doesn’t tend to lead to happiness or blessedness; on the contrary, it tends to mean, precisely because it’s so easy to solve your practical problems, that all your problems are now spiritual, and the chief among those problems is the overwhelming emptiness in your soul, because wealth cannot substitute for love, meaning, or faith.

So what should the rich do?

Today’s reading – “woe to those who are full now” and the line from the Magnificat – “the rich will be sent empty away” – point us in the direction of voluntary self-emptying. And Christians have a name, and a model, for this.

The name is kenosis, which is simply the Greek word for “emptying”. And the model is, of course, Jesus Christ, who gave up ultimate power as part of the Godhead, and “emptied himself, taking the form of a slave,” as the letter to the Philippians puts it, in order to be part of humanity and save us. Ever since, Christians have been called to imitate Christ’s kenosis.

This can take many forms. It can mean withdrawing from the world and joining a monastery. It can mean taking on hard and unpleasant duties, such as caring for a sick loved one, in a spirit of cheerfulness and compassion. Or, for those who have enough material possessions that it is easy to insulate themselves from the presence of God and the hardships of the world, it can mean deliberately choosing to give up some of those possessions and the security that comes with them, to reduce the amount of insulation between themselves and the brutality of life, to be sent empty away before God does the emptying for them.

Because the thing is, in insulating yourself from the brutality of life, you also insulate yourself from its beauty. You deny yourself the chance to feast with those who are genuinely hungry, to laugh with those who have honestly wept. When you empty yourself, you make space for God to fill you. Even God saw the value of emptying Godself in order to make more room for what was ordinary, vulnerable, and human.

It’s well known that money does actually buy happiness up to a certain level – the level where you’re not worrying about basic necessities and you can afford a few fun things and simple luxuries. Above that, though, it’s incredibly dangerous.

A few weeks ago – somewhere on the internet, because of course I can’t remember any more specifically than that – I read about a theory that when you get up to billionaire level, even the biggest, splashiest purchases only provide a dopamine hit equivalent to an ordinary person pulling the lever on a 25-cent slot machine. Which perhaps explains something about current world events.

Far better to be the ex-wife of the founder of Amazon, who got half his money in the divorce and promptly set about giving it away.

Nobody listening to this sermon is a billionaire, thank goodness. And our parish is moving in the direction of more economic diversity, not less. But all of us can hear Luke’s provocative, practical beatitudes, and think: am I full right now, or empty? Well-fed, or hungry?

“Woe to you who are rich,” says Luke’s Jesus, “for you have received your consolation.” Is that really the consolation that we want, those of us who are comfortable – to be cut off from the concerns of ordinary people, desperately trying to find meaning in ever-increasing spirals of consumption? Or should we be looking to move in the other direction?

One way or another, the rich will be emptied. Either God will do it for them – or they can choose to do it themselves, engaging in deliberate kenosis, imitating Christ, making room for God to empty them – and then fill them up again with the things that make life worth living: community, creativity, learning, sharing, and joy.

Amen.

Leave a Reply