All Saints’, Dorval

March 2, 2025

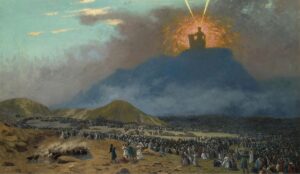

Jean-Léon Gérôme, “Moses on Mount Sinai,” c. 1897.

A month ago, I led All Saints’ second annual midwinter retreat. The theme was “Holy Darkness,” and we looked at the ways that light and darkness have been correlated with good and evil, respectively, in the Bible and in how the Bible is interpreted. Associating light and daytime with good and with God, and darkness and night with evil and sin, is so automatic at this point that we barely even notice we’re doing it, so it’s a good idea to take a second look and realize that things are far more complicated than that.

And as I looked through the Bible for places where it speaks of darkness, a remarkable theme emerged: starting in the story of the Exodus, God lives in the darkness.

After the people come out of slavery in Egypt, cross the Red Sea, and begin wandering in the desert, they stop and set up camp at the foot of Mount Sinai, and Moses ascends the mountain to speak with God and receive the law. The peak of the mountain is wrapped in clouds, smoke, and darkness, and God lives inside the darkness and speaks to the people in thunder. (Fairly soon, they find this too much to handle and tell Moses that he can speak to God on their behalf and report back.)

As one might expect, it’s not a straightforward process. Moses is on the mountain for forty days and forty nights, and by the time he comes down, the people have given up on him and are worshiping a golden calf that they’ve created by melting down their jewelry. Moses throws a fit, breaks the stone tablets of the Law, and goes back up the mountain to try again.

And that’s where our reading today comes in. “As he came down from the mountain with the two tablets of the covenant in his hand,” he’s doing it all for the second time. God has made the skin of Moses’ face shine in order to underscore for the people that he truly is chosen by God, and that they should believe him, and accept the Law and Covenant that he is bringing to them.

But God still lives in the darkness.

Going over this story in detail reveals how many exact echoes of it Luke has built into his account of the Transfiguration. Jesus and his three closest friends go up the mountain; they meet God, and Jesus is transformed in dazzling light, like a more extreme version of what happened to Moses. Moses himself appears, as does Elijah, connecting this experience to that of the prophets who also encountered God in darkness and storm. When they “speak of his departure,” the Greek word used is literally exodos, from which we derive “Exodus,” the name of the book and the term used for the whole process of coming out of Egypt and receiving the Law.

As Moses and Elijah are departing, “a cloud came down and overshadowed them, and they were terrified as they entered the cloud” – just like the people of Israel watching Moses go in to speak to God. And just as on Sinai, on this mountaintop God speaks and tells those who hear to listen to his chosen one – in this case, the new Moses, God’s own son, Jesus.

So in these stories, it’s not that light represents God and darkness represents evil or sin or even the absence of God. God is in the darkness. The light represents God’s approval, it shows whom God has marked out as the one who can speak for God, but where God is, is in the darkness. There is no part of these stories from which God is absent.

And it’s here that once again I have to footnote the distinctly unhelpful reading from Paul, which uses the image of Moses’ veiled face to take a smack at the Jews of Paul’s day for not immediately acclaiming Jesus as the messiah.

Three weeks after the “Holy Darkness” retreat, last weekend I led a workshop for the Lay Readers on medieval interpretations of Scripture. I would love to recapitulate it here, but it took four hours, so I’ll spare you that. But one of the things I mentioned in that workshop was St. Augustine’s principle of biblical interpretation, which is that all readings of the Bible must conform to the rule of charity. If it doesn’t promote love of God and others, it’s a false reading.

So once again, I point out that Paul was a Jew criticizing other Jews, which was tiresome of him but at least somewhat understandable; but it is not all right for us as Christians two thousand years later to use these passages to denigrate Jews and their relationship with God and scripture. Our responsibility is to read scripture always in light of the two great commandments, love of God and love of neighbour.

Our reading today ends with the three disciples amazed to the point of speechlessness by their experience on the mountain. What happens next, after their descent, is a scene of chaos and desperation: a man begs Jesus to heal his son, who has seizures. The other disciples have unsuccessfully tried to cast out the demons they believe are causing the convulsions. Jesus rebukes them all – “You faithless and perverse generation, how much longer must I be with you and bear with you?” – but he does heal the boy, to the amazement of all.

Once again, the parallels with the story of Moses and the Law are clear: the one who intercedes with God comes down from the mountain and encounters not gratitude and faith, but chaos and despair as people have turned away from God.

It would be easy to see here, again, a simple dichotomy like that of light and dark: the top of the mountain is where God dwells and where great moments of revelation happen, while the mountain’s foot, where the crowds are, is the realm of confusion where God struggles to be heard. But just like the split between light and dark, this would be an oversimplification. God is present in both places, just like God is present in both light and darkness. Things may be harder at the bottom of the mountain, but that’s where we live, and God would never abandon us just because life gets kind of messy.

God heals the child with seizures. God gives the law and remains faithful even when the people reject it. God dwells both on top of the mountain, near the heavens, and at its foot, amid the crowds and chaos. God dwells in the darkness but clothes God’s chosen one in dazzling light.

This episode of the Transfiguration is a crucial turning point in the overall arc of Luke’s gospel. From here on out, Jesus’ face is set toward Jerusalem and the coming crucifixion.

Having read this passage this way, we can be sure that even in the darkest and most chaotic moments of the story to come – in the shadows under the trees in Gethsemane (when the disciples fall asleep just as they do on the mountain!), in the middle of the night in the high priest’s courtyard when Peter denies Jesus, in the crowd as they howl for Jesus’ blood, during the terrifying hours when the sky darkens as the Son of Man dies, and in the bleak despair of the tomb – though Jesus may cry out to God asking why he has been abandoned, God is still there. Jesus is just as much God on the cross as he is while shining like the sun on the mountaintop.

Today we celebrate the Transfiguration. Wednesday, we enter into Lent, and the journey to the Cross. But we have nothing to fear, because even in chaos and darkness, God is there.

Amen.

Leave a Reply